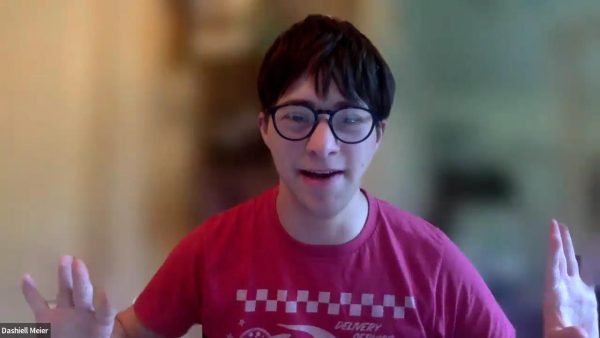

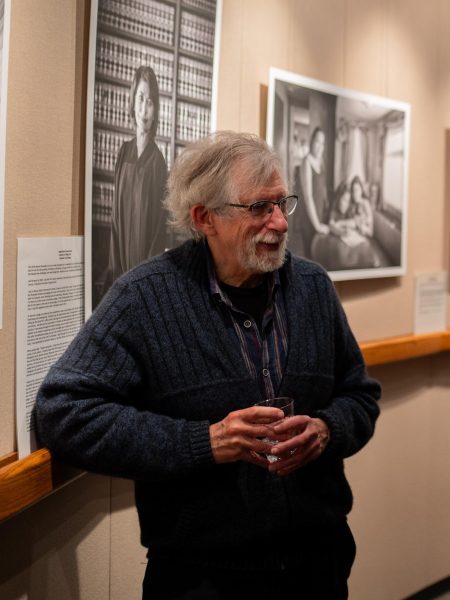

Dr. Tom Chatfield on Fake News, Critical Thinking, and the Internet

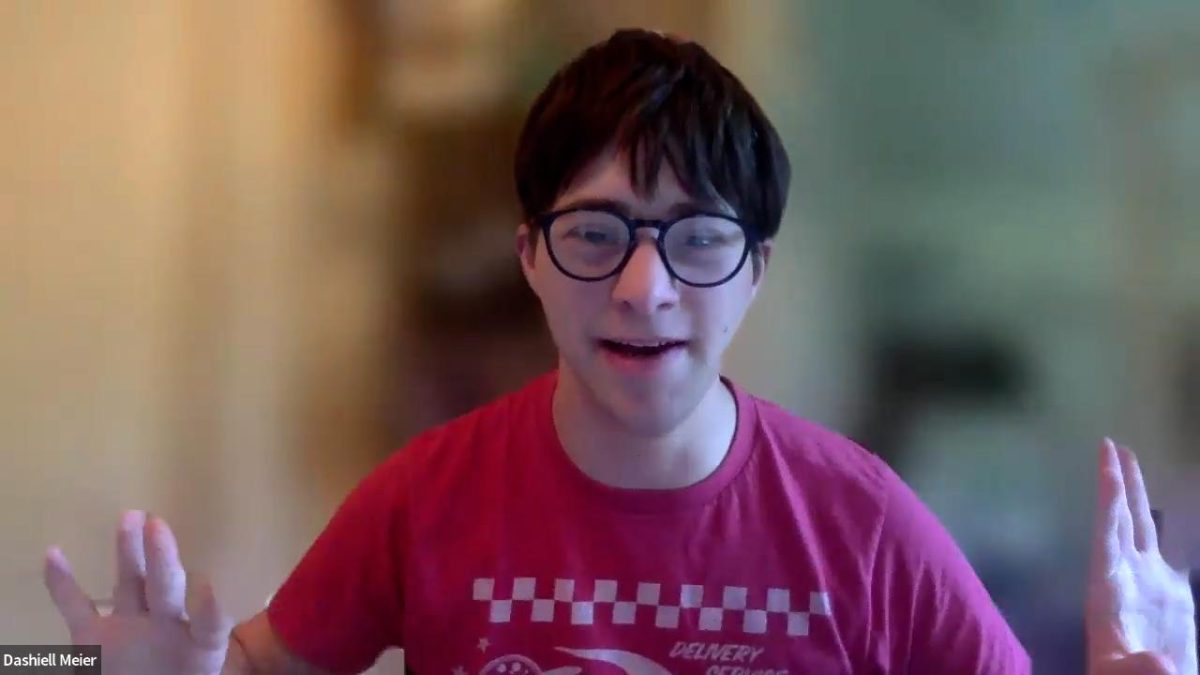

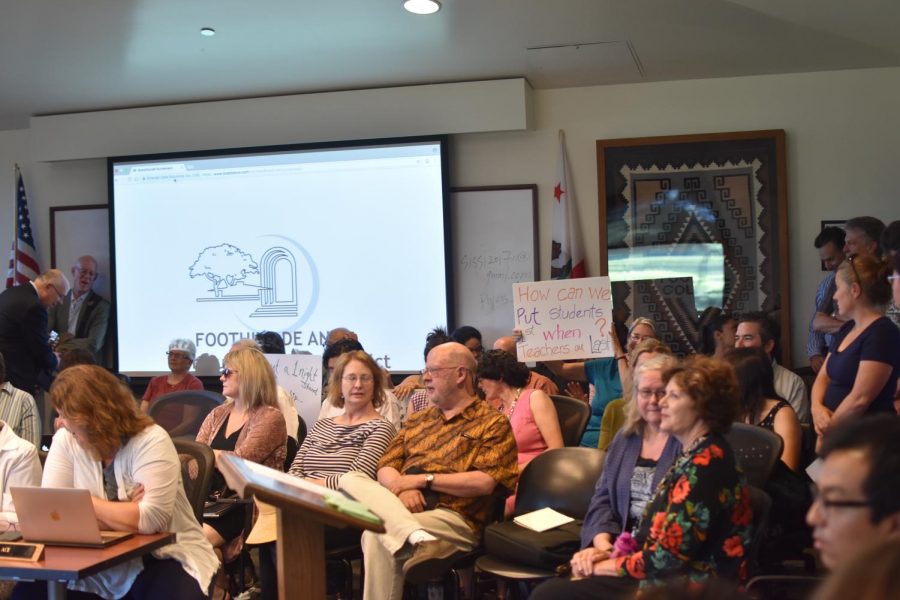

Dr. Tom Chatfield, a philosopher of technology and bestselling author, visited Foothill on February 5th to discuss fake news, disinformation, and critical thinking in public discourse — a subject that Dr. Chatfield recently wrote a book on. I spoke with Dr. Chatfield extensively after the event about his thoughts on rhetoric in the information age.

What would you say is the biggest issue around critical thinking facing the public today?

I think one of the great problems is that people don’t have the time and the space and the tools for thinking twice about things that matter. And I think at the moment, it’s particularly difficult because we are bombarded by very seductive information. And the…mass manipulation and exploitation of emotion is a fundamental business model — and political model — in the information age. And in many ways, technology and events have moved much faster than our habits and than our education system.

There’s a tremendous amount of very great positives in our unprecedented ability to collaborate, to hear a greater diversity of perspectives than ever, and to conduct investigations of ourselves and our world. But alongside this, there are huge opportunities for those who want to select bits of evidence and argument that fit their worldview, and who want to manipulate others, and who want to use what we know about people and how we come to beliefs, not to improve our understanding of the world, but to improve the ability of certain groups to wield power or make money. And so I think we are … grappling with the gifts and the hazards of our technology and our knowledge. … And I am thus, among other things, trying to help people to have habits and tools and strategies that help them take ownership of their own thoughts, and become more confident and critically engaged users of information systems.

Has your perspective on critical thinking changed at all since the rise of fake news and Donald Trump?

My opinion is changing all the time because there’s a great deal of uncertainty out there. I don’t think it’s helpful to enter with a kind of fixed position about what needs to be done, or what the problem is. I’ve certainly come to feel that a line I quoted in my talk is very important, that ‘you cannot reason people out of a position they didn’t reason themselves into’, and that unfortunately, the idea that fact-checking and fighting fake news with truth is what we need to do [as] a solution to our problems…is very naive, because it’s not a very good description of how and why people believe things and do things.

I think the better description lies in an understanding of how the beliefs that we show allegiance to and act upon are … very closely bound up with our identities, very closely bound up with who we believe are the people like us, the people not like us. … If we want to deal productively with this, we also need to look at the incentives that exist in the information systems we use. And to some degree, we need to get a lot better at listening to each other, and a lot better at recognizing the circumstances under which we can help each other to find common ground, to make better judgements, and to synthesize different points of view.

You mention that you can’t really reason someone out of a position they didn’t reason themself into. Would you say that the people who have reached a perspective that is not built on reason are sort of a lost cause?

No, I wouldn’t, no. Because interestingly, I don’t think there’s such thing as a perspective built on reason. Because no perspective on the world is built on pure reason…what you think those facts mean, and what your values are, and what you think is right and wrong, can never be derived purely from reasoning. And I think, unless you can spot that difference, you’re going to fail to engage with people who come from a different position from you. That doesn’t mean you should always engage with everybody. You know, I think there are certainly people and views and circumstances which trying to engage empathetically with is not helpful. But, it’s a big blind spot, I think, to believe that not only are you reasonable — which may be true — and not only are you in possession of facts — which may also be true — but then to believe that what you think ought to be done is also objectively true.

The rise of fake news can be attributed in many ways to the algorithms of social media. How much of the responsibility for resisting this type of propaganda lies with the platform versus the consumer?

I would say a great deal of responsibility lies with the platform. And to their credit, platforms of all kinds are beginning to grapple with what this means because it has caught many people by surprise. And there are some very deep tensions to be negotiated between the business models and … social good, and also between what it means to be a publisher and what it means to be a platform. I guess one of the problems is that it is not about what ordinary … users do, it’s about what a minority can achieve when they game the system. And there is intense evolutionary pressure online and on platforms where so much is going on, that information with a great … degree of persuasiveness or virality is being created in an evolutionary hothouse if you like…

Interestingly, I think…going forward, it’s going to be more and more a question of human and machine systems working together. So for example, we’re seeing now the emergence of very very convincing fake video and audio footage that essentially can be generated by almost anyone in a short length of time…

You have this interesting situation in which, you know, machine-generated and machine-perfected disinformation is then in combat with machine-systems for spotting the tell-tale signatures of manipulation and disinformation and so on. And so, I think, whatever happens, we need to move beyond demonizing platforms and start thinking about algorithmic social responsibility, and codes of practices, and marks of quality, and reputation and so on, in a much more long-term joined-up way.

You’ve done a lot of work on like the internet and on internet culture, but you’ve also done some work on games. I was wondering, how would you say that phenomena like Gamergate in 2014 sort of fit into this development of the rhetorical sphere on the internet?

So, around games, we’ve had some very toxic subcultures. And I think games and sports, in general, have long tended to tap into and produce very tribal loyalties. … [Games are] very compelling as … things that bind people together. And wherever you have this very … intense binding, you have the potential for very tribal and maybe very aggressive patterns of behavior around it.

I guess one of the interesting things for me as a general phenomenon, which I would link to, for example, the MeToo hashtag, is that more and more, phenomena that happened in one kind of particular domain or zone, are now being outed and displayed to the world. And you could say something very positive about this — that it is much harder for a kind of, an abusive culture that exists in a particular niche to stay hidden in that niche. And it’s much harder for there to be a conspiracy of silence or indifference around it in society at large, so suddenly … we’re talking a lot about the way that, you know, powerful insider clubs have abused [people], and one could certainly say this is one of the great positives of tools of social media — that they can allow people to know that they are not alone, where previously, they may have felt there was no way in which they could be heard or believed, or the professional or personal risks were too great [to come forward].

It doesn’t mean that everything magically becomes okay and so on, but I think one of the great claims of technology has always been to know that you are not alone is a powerful thing. And it can be a powerful thing for good and for redress, and it can be a powerful thing for causing harm.

Games interest me as well because they are often bound up with how young people first experience technology… And I think this means that there’s often a great responsibility around how we play with and through technology, and whether with our children and each other, that play is something that allows us to safely explore how we ought to treat each other socially, and how we form communities of allegiance and loyalty and so on, or whether it is tribal in a very closed sense … one of my hopes is that expressive, generative play, and what goes with it, can be a large part of young people’s experiences of technology, and that games of domination, if you like, are not their defining experience of becoming users of tech.

Moving forward, what steps would you suggest media organizations take to help encourage critical thinking?

I think the idea of offering tools can be very powerful … sketching and showing and demonstrating the methods by which you investigate with an open mind what is really going on. Media organizations, I think, are really doing a tremendous amount that’s positive in this arena, because we see all the time, the desire to find out what is really going on.

[There is a] saying that news is what somebody, somewhere doesn’t want you to say, and the rest is advertising. … I think Lord Northcliffe originally said that…I guess an interesting question is how knowing what is really going on can be something that is evidence based rather than something that is about conspiracies. And I think transparency is a very big deal. I think working with data organizations, working with… government, working with lots of different stakeholders, to more transparently open up data and information about what’s going on and so on, can bring great benefits, because to some degree, shedding light on things can make it less likely that a conspiratorial account can take hold…

There’s very serious questions to be answered as to … how you persuade and reach out to people from … [a] greater diversity of viewpoints than you currently might kind of write for and speak for. And I think, you know, to go to the places where people are sort of talking the language that they talk in, to recognize and respect where they come from, to engage in dialogue, to leave questions and to practice empathy and so on — these are all very hard things to do. But they can have great value.

I think above all, seeking better to understand the incentives in information systems is a big deal, and I think rather than demonizing platforms, which can be rather unproductive, I think working with them, working with their data, working with machine tools that can assist people, and seeking to deserve trust, and to find business models that are more sophisticated than just, ‘how much attention can we win at any cost?’ I think all of this … has a large part to play.