“Being Mortal” Review: A Critical, Existential, and Thought-Provoking Read

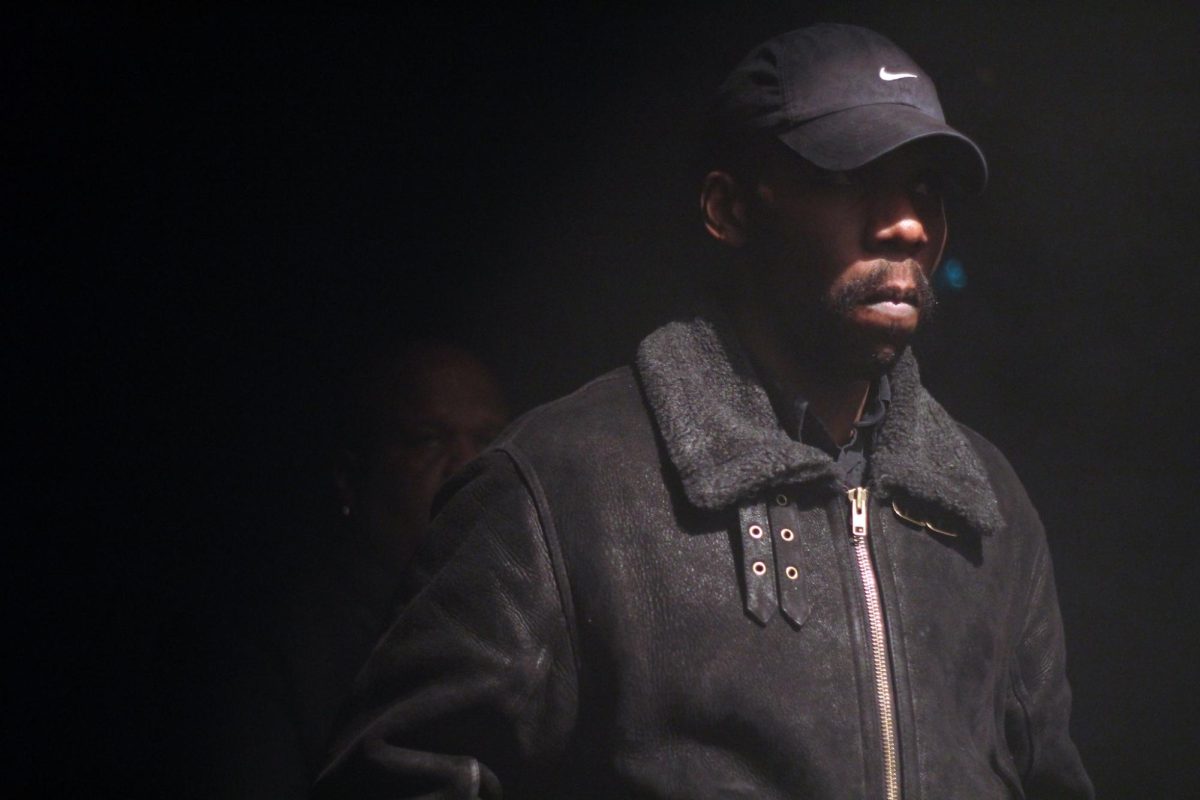

Amar Karodkar vie Wikimedia Commons

Atul Gawande

Current coverage of healthcare focuses on insurance and longevity, while ignoring what may affect the patient the most most: mental health. “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End,” a book by Atul Gawande, effectively argues that the further medicine advances, the further it strays from its original purpose of ensuring a patient’s well being. In order to prevent such regression, doctors must not only learn to view patients as individuals, rather than diseases with uniform solutions, but also alter their perception of well-being to include and emphasize a patient’s mental health. “Being Mortal” covers different aspects of dying, such as accepting death and living well in old age, through the lenses of psychology, policy, and medical practice –providing the reader an extremely thorough look at the current state of medicine in regards to longevity and Gawande’s vision.

Gawande “practices general and endocrine surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital” and is a professor of both Health Policy and Surgery at Harvard University. This unique position as both surgeon and professor of policy allows him an understanding of how doctors are taught to approach dying, and how current practice materializes in patients’ healthcare.

The book consists of eight chapters, each of which focus on a certain intersection of aging and healthcare. Every chapter begins with an anecdote, and an explanation of what it reveals about healthcare policy. The chapter “Letting Go,” for example, describes the story of a woman with an incurable cancer, and then asks the reader at what point a patient should cut their losses. Should one accept their inevitable death, or go through yet another exhausting operation, only to die soon after? This format places the reader in the patient’s shoes, asks them to ponder their wants and needs, and evaluate how they would be treated in today’s policy — thought-provokingly revealing that these needs may be at odds with the institutional norms.

Gawande’s ability to interact with the reader is what makes “Being Mortal” more than simply informative. His tone is conversational and neutral, prompting the reader to logically come to their own conclusions about the topic presented, rather than project their gut response on an emotionally charged topic. He also does not shy away from getting into the weeds on a multitude of topics, from healthcare policy to psychology theory, yet does so in a way a reader of any background could understand. This is perhaps one of the important things about “Being Mortal.” If choosing how to live and how to die is the last and most important decision one will make, and it’s one everyone will make, it’s crucial that a possibly transformative view of it be as accessible as possible to those with and without access to professional advice.

Hearing that death may be better than life is shocking, if not offensive in our longevity-focused culture. Though the book does heavily discuss policy more specific to the lives of the elderly, it is a treat for any existentialist, policy nerd, or anyone with aging loved ones. “Being Mortal” asks one to set aside their preconceived notions aside, and consider what really matters at the end of the day. Is it healthcare costs, quality of life, physical ability, or mental health? That’s up the reader to decide.