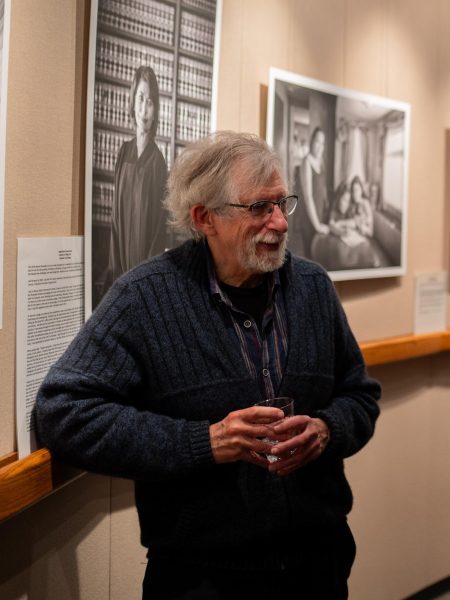

IEW: Dorothy Ngutter of the US Department of State

As part of International Education Week, Dorothy Ngutter of the State Department visited Foothill College to present on her career as a diplomat and on what it takes to work in foreign service. Ngutter is currently the Diplomat in Residence of the Northwest region, responsible for outreach and recruitment on State Department programs in Alaska, Northern California, Oregon, and Washington.

Ngutter began her presentation by discussing how she found her way into her career. After majoring in Communications and working on the technical writing team of a software company, she was unsure about staying in the field.

A nascent fellowship from the US Department of State allowed Ngutter to pursue a graduate degree while preparing her for a career as a foreign service officer. When she applied for the fellowship, Ngutter didn’t quite know what the job entailed, but hoped her history of living overseas and her multilinguality would make her a good candidate.

The foreign service draws its members from candidates with varied educational and experiential backgrounds. It is not uncommon for Foreign Service Officers to begin their college careers unaware of where they’ll wind up and pursuant of a variety of majors. Though Ngutter spent more time in higher education in preparation for her international career, she also noted that there are no specific educational requirements to go into the foreign service. The only requirements are that you must be a US citizen between the ages of twenty and fifty nine, pass through the interview and examination process, and obtain medical and security clearances.

According to Ngutter, the learning curve for each assignment can be very steep: she described it as often feeling like “drinking from a fire-hose.” Although she emphasized the rigor and comprehensiveness of her training — she initially spent nine months taking training courses and learning French — she also insisted that it’s impossible to cover all the bases. During her first assignment, Ngutter worked in both in consular services, where she facilitated visas and travel applications for US Citizens, and as a human rights officer. On one occasion, though, Ngutter gave a speech on behalf of the US Ambassador to Mali at the opening of a new health clinic, entirely in French — an experience hard to anticipate.

After Mali, Ngutter was assigned to a US mission to NATO in Brussels, Belgium where she was an assistant press attache. A significant portion of her career was spent in Washington, DC; she worked at the Operations Center keeping tabs on foreign affairs worldwide, spent two years at the Peru Desk as a departmental liaison and the main contact for the Peruvian and the US Embassies, and worked in the Office of the Under Secretary for Political Affairs as the special assistant for Africa and global issues. Before settling into her current position as Diplomat in Residence, Ngutter spent time working at the US Embassy in Ankara, Turkey, and took a fellowship via the National Security Affairs Fellowship at the Hoover Institution, where she spent the year doing research.

The variation present in Ngutter’s roles and responsibilities is due to her application as a generalist. While generalists enter either consular, public diplomacy, political and economic reporting, or management tracks, there’s no guarantee that assignments will always fall under the track of choice. Those who enter the Foreign Service as specialists, on the other hand, have specific skills, and often include medical personnel, doctors, and information technology workers.

Despite the fact that she spoke Spanish and Swahili, on “Flag Day,” where new officers receive their first assignments, Ngutter was handed the flag for Mali, which speaks predominantly French. An audience member asked if this was random; she responded by describing the assignment process. During her training, Ngutter was given a list of as many countries as there were candidates and listed them by her own personal priority. Candidates for each country were assigned based on their priorities, skills, as well as the needs of the Foreign Service.

There are three parts to the application; the foreign service officer test, offered three times annually, is the first step. The test is standardized, and can only be taken once each year. If the test is passed, the candidate moves onto an essay portion, which gets reviewed by a Qualifications and Evaluation Panel. In this area particularly, applicants will want to be able to cite demonstrative examples of the thirteen dimensions, “soft skills” sought by the department, including oral and written communication, initiative and leadership, and cultural adaptability.

For students, internship programs are also available. Typically, summer internships last ten weeks are in Washington, D.C. or overseas, and are unpaid. The application process begins early, and is usually due nine months in advance of the internship.

Ngutter’s varied career speaks to the opportunities available in the US Department of State. Despite its intensive application process and demanding assignments, dedicated applicants of all educational backgrounds interested in international affairs can expect a difficult but rewarding career path.

More information on careers in the US State Department can be found here.