World Perspectives: Foothill Professors Examine Trump’s First Year

On November 8th, 2016, President Donald Trump was elected into office — an event discussed extensively through an American lens for each day and month to come. A year into the presidency, a panel of Foothill professors with diverse perspectives organized to give a global view at the Hearthside Lounge last Wednesday.

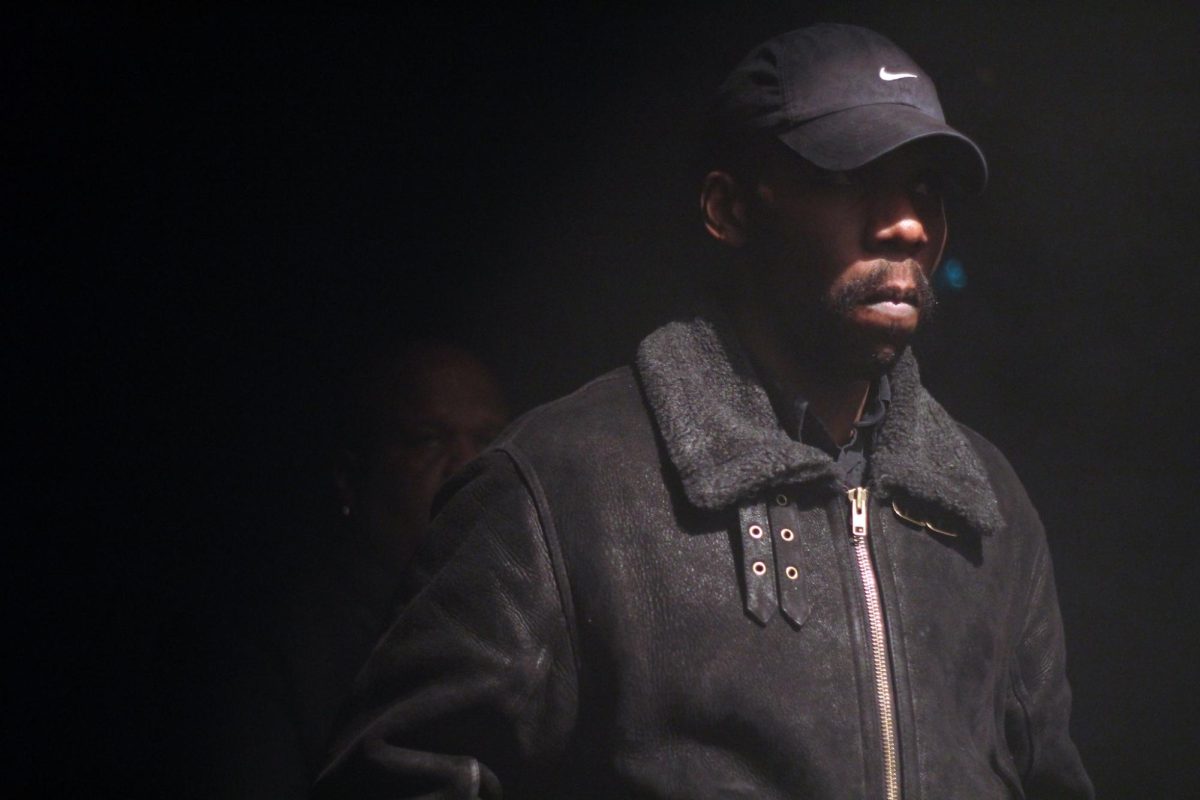

Since the election, the atmosphere had certainly changed. A year ago, a panel was initiated days after Trump’s shocking win; the room had overflowed with people — crying, shaken, and with no idea what to expect. Mark Harmon of the Political Science department spoke that day, doing all he could to simply calm the crowd.

Last week, the room calm and half-full, Harmon once again initiated the conversation. He began by posing questions: why had Trump been so unsuccessful? Trump had promised a border wall, the replacement of Obamacare, and tax reform, yet none of it had manifested into actual legislation. Answers ranged from Trump’s lack of experience in politics, newfound opposition and political engagement across the country, and a profound difference in the way the administration functions on the world stage in comparison to other foreign leaders.

This could be the result of multiple factors: while President Trump certainly hadn’t had the experience to prepare himself for a political position, more importantly there has been opposition to these promises.

Meredith Heiser, a Professor of Political Science spoke next, delivering an eye-opening German perspective. In Germany, she explained, a far right party had surfaced. This anti-immigration, anti-globalization party, Alternative for Germany, had “garnered 13% of the vote” in the 2017 Federal Elections. Heiser de-escalated the alarm such a statement may have induced: the far right wing receiving such a significant portion of the vote was actually to the advantage of the left. According to Heiser, Political parties in Germany tend to overlap more causing “extremes” to be less extreme as they would be in the United States. Heiser explained how American political parties are more polar, and tend to harbor intense animosity towards each other.

The popularity of an anti-immigration platform wasn’t too shocking upon further inspection either.

“Germany took in a million immigrants — forty times the number of refugees the US did,” said Heiser.

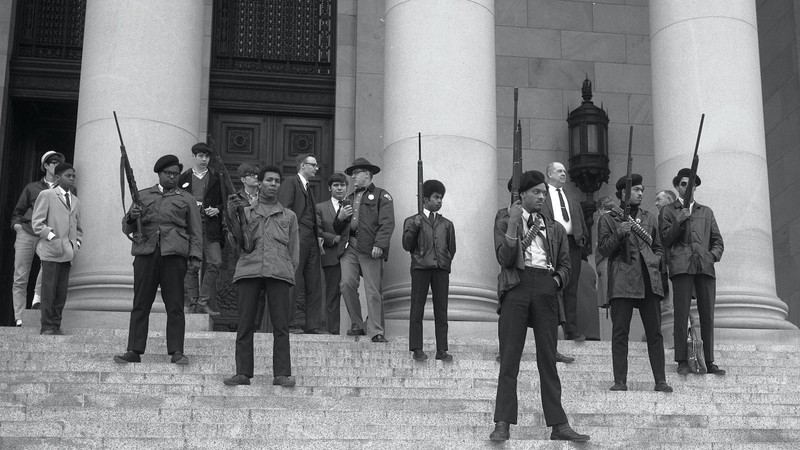

She went on to highlight the impetus behind anti-establishment politics. Extremes, according to her, gained support as citizens grew sick of the way their countries were run — they craved new voices.

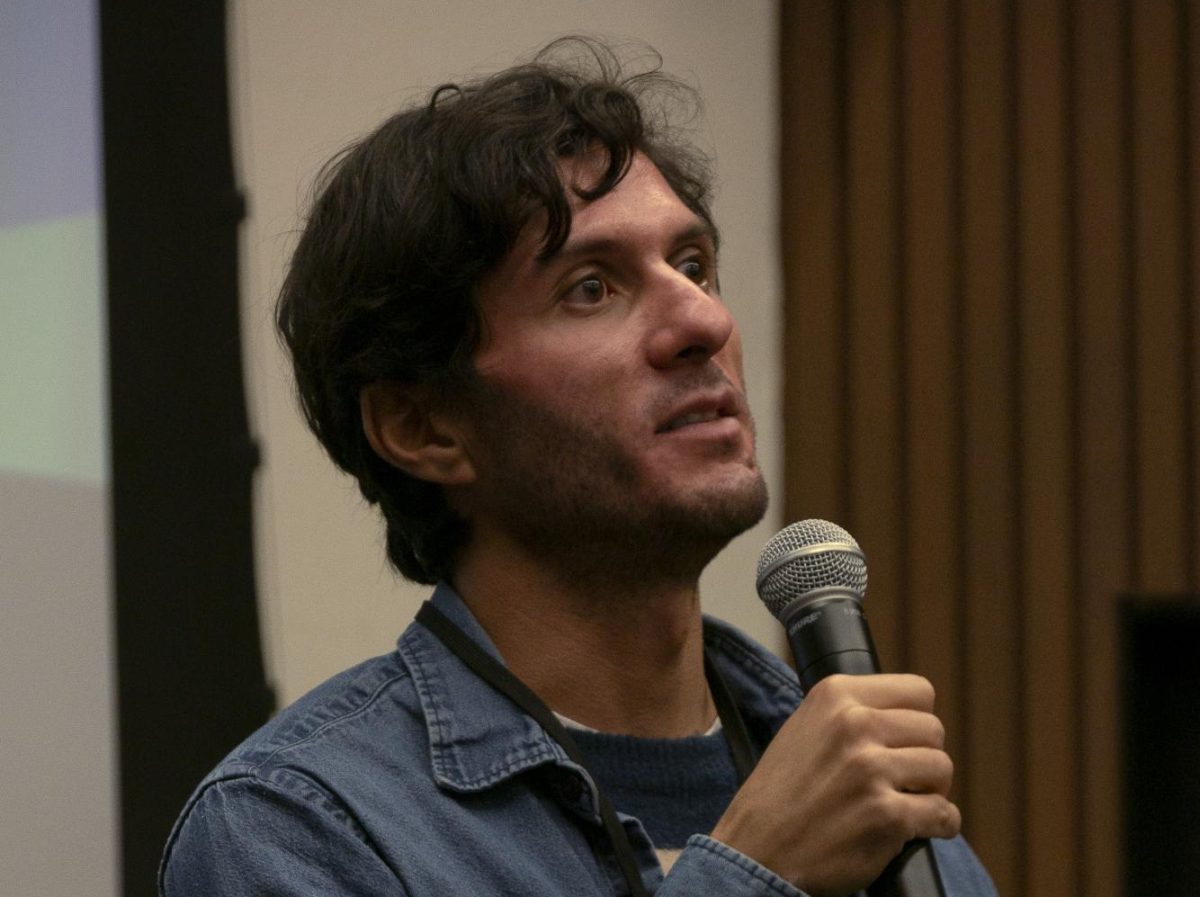

Leighton Armitage, professor of Political Science, represented France, where he had been educated, in addition to China. “Macron is known as the Trump whisperer,” he began, addressing the amusing, but surprisingly true, rumour about French President Emmanuel Macron. Armitage explained that Macron has always been able to get through to Trump, even if he and a majority of French citizens do not entirely respect him.

He traveled from this anecdote to discuss various foreign relations policies: the Trans Pacific Partnership, the North American Free Trade Agreement, the Iran Nuclear Deal, and the Paris Climate Accords were all thrown into chaos by the Trump administration. From Armitage’s standpoint, the US seems to be rejecting the rest of the world — we are on, in his words, “a train towards isolation.”

“Will this benefit us in the long run?” asked Armitage. The audience was still. “I don’t think so.”

Patricia Gibbs, Professor of Sociology, concluded the talk with a lively presentation from a Canadian-American sociological perspective. The three speakers before her had focused primarily on Political Science and Economics, giving Gibbs’s speech an especially unique perspective.

Side by side, she presented Canada’s views on issues that starkly contrasted with America’s. Among the most extreme in difference were health care, climate change, free trade, immigration, gun control, and wealth distribution. American citizens and policymakers have long been divided by the aforementioned list of issues; to Canada, she informed the room, that divide was ridiculous. Gibbs suggested that Canadian values differ from America’s in key ways, and that they might benefit the average American were they examined.

There has been opposition. The words of the first speaker, Harmon, remained and resonated in the atmosphere through the rest of the discussion. Mark Harmon told us he had been afraid, just as everyone in the room had been, days after Trump’s win.

But he also told us he should not have been.

“Federalism and separation of powers,” emphasized Harmon, are the Constitutional basis for resistance. He repeated these words throughout his speech while outlining their numerous effects and significance throughout the events of the last year.

Trump proposed a travel ban and the courts struck it down. Trump cracked down on immigration and California became a sanctuary state. Trump encouraged Congress to “repeal and replace” Obamacare and it didn’t pass the Senate.

Trump was not elected in a vacuum. “Federalism and the separation of powers”, as well as attention from both the domestic and international community have resulted in the failure of most legislation emphasized throughout his campaign