It Can’t Happen Here at Foothill College

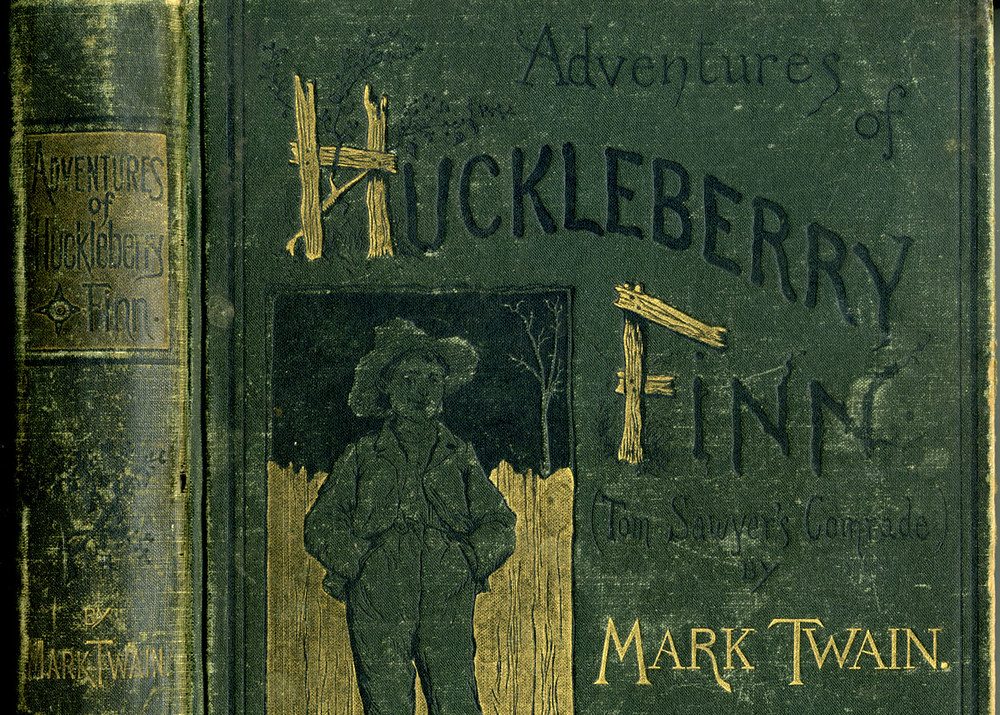

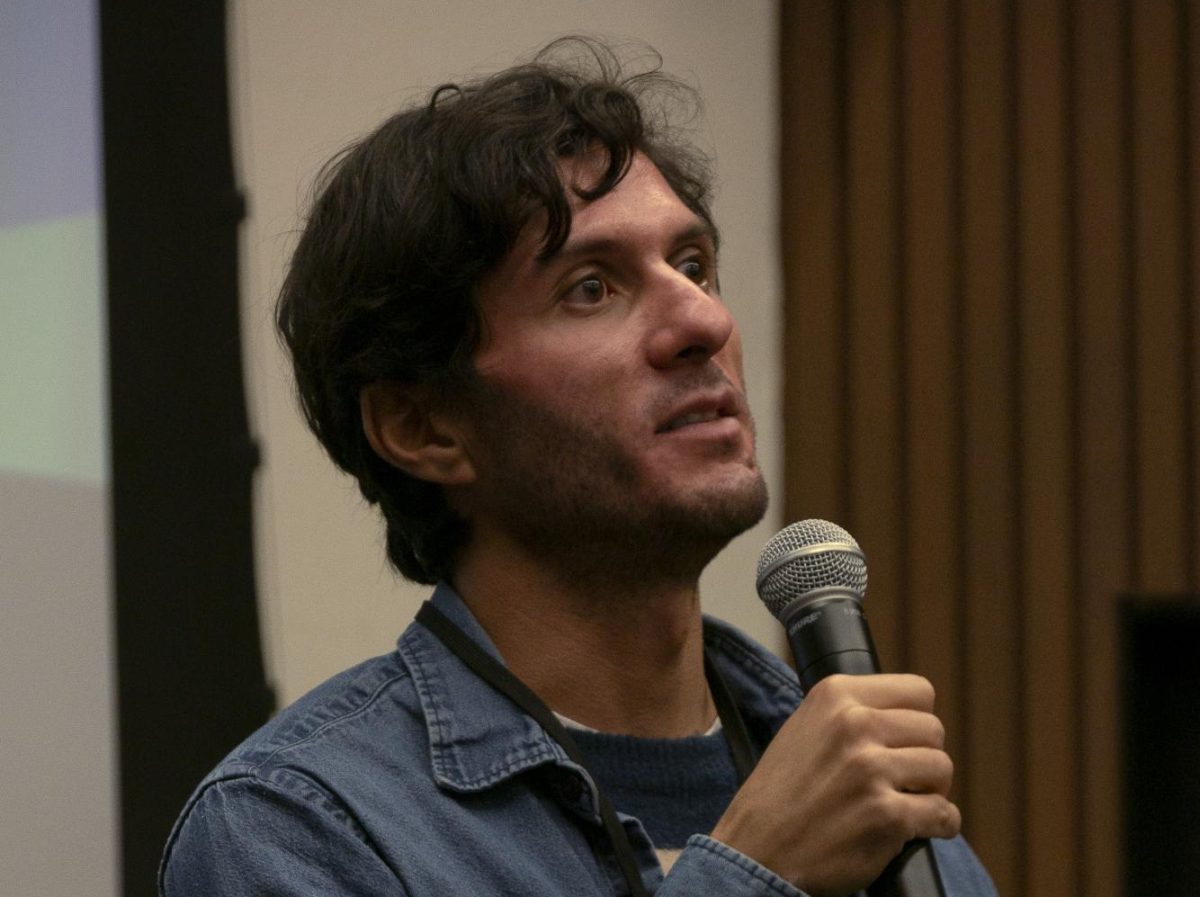

“A blind mule has a greater chance of getting elected!” exclaimed Doremus Jessup (Vic Prosak) in regards to the candidacy of Buzz Windrip (Thomas Times), a controversial populist presidental candidate. This and other parallels of doubt, vindiction, and excitement over a political hothead, seemingly impossibly similar to our current political climate, were just one aspect of what made Foothill Theatre Arts’s production of “It Can’t Happen Here,” adapted from Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel of the same name, a roaring success.

The play follows the politically liberal Doremus Jessup, editor of the local newspaper, and his family and community as they navigate through the conflict and turmoil that begin upon the emergence of Senator Windrip, who runs his campaign on the promise of five thousand dollars for every person, on a national scale. The play effectively encourages audience members to view situations from other lenses and focus on dialogue and conversations that achieve progress.

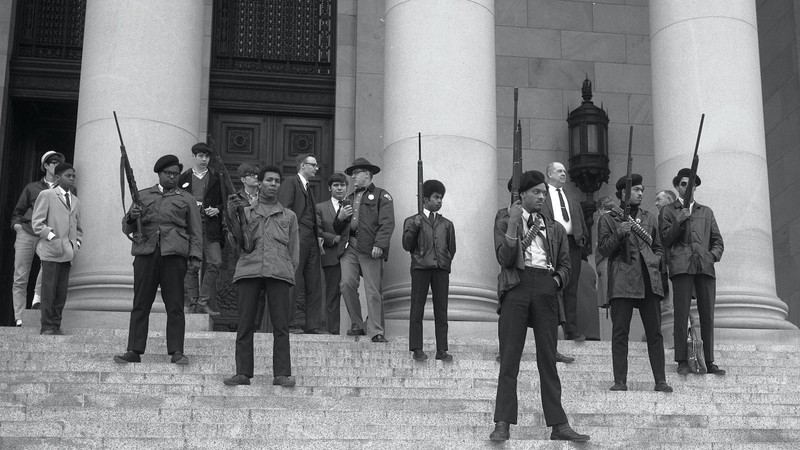

An obvious way in which productions are able to speak to their audiences is through involving them, thereby forcing viewers to consider what they would do were a theatrical situation real life — and “It Can’t Happen Here” achieves this excellently. Each and every person is forced to take a side: throughout the performance, members of the ensemble held up signs, signaling for boos, cheers, or applause.

In the opening scene, taking place at the local rotary meeting, audience members cheered and applauded when characters spoke passionately about reinstating law and order and supporting the good, Christian militiamen, chapters of which had sprung up all over the country. Given the continued relevance of many of the issues discussed, I often felt a jolt applauding for ideas that I fundamentally disagreed with — but it made the experience as an audience member all the more realistic.

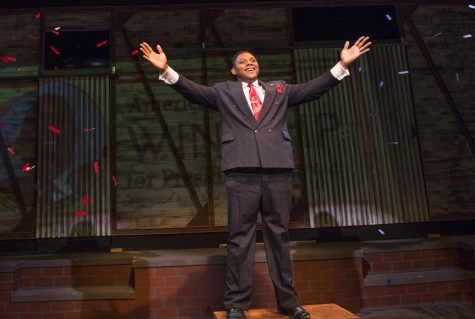

This level of involvement soared to new heights at Buzz’s first appearance in the show. During this particular scene, I was enraptured by such a high level of overt patriotism that I was quite unaccustomed to — Windrip spoke in a booming voice, was all smiles, and was accompanied by patriotic music and red, white, and blue confetti which rained down upon the end of his speech. The audience cheered, right on cue; I was even handed a souvenir-sized American flag to wave.

Whereas previously Jessup criticized Buzz for his constant focus on money and aversion to facts, post-rally he debated if Windrip was really “that bad” of a candidate; having been swept up in patriotic fervor, he couldn’t remember a word said in the entire speech. After the show, I asked Thomas Times about his character, and whether if during the production he, too, felt swept up in the grandiosity of it all: “Buzz is really good at manipulating people and getting to know what they really want, so it’s all about feeling the audience…to get people to vote for you, you have to get them to like you…these people can get me elected, my job is to connect with every single person in this audience.” For me, at least, he succeeded — for a moment, I wasn’t a theater-goer, but a member of a rally. The construct of the play melted away, and I felt like I was part of this great big idea.

Ignorance may have also played a part in this enthrallment: the lack of elaboration on Buzz’s policy choices and ideals lead me to feel like I didn’t know the candidate well at all. This is to be expected — I obviously wasn’t going to gain as much technical information about a (fictional) candidate in a two-hour theatre production than I did in last year’s highly-publicized presidential election. In all fairness, though, I feel that this speaks to the idea that these highly nationalistic displays are easy to fall into, especially when voters don’t know their candidates, or the opposition, as well as they should. As someone who tries to keep up pretty well with candidates and policy, it was groundbreaking for me to see the role that unintentional ignorance played.

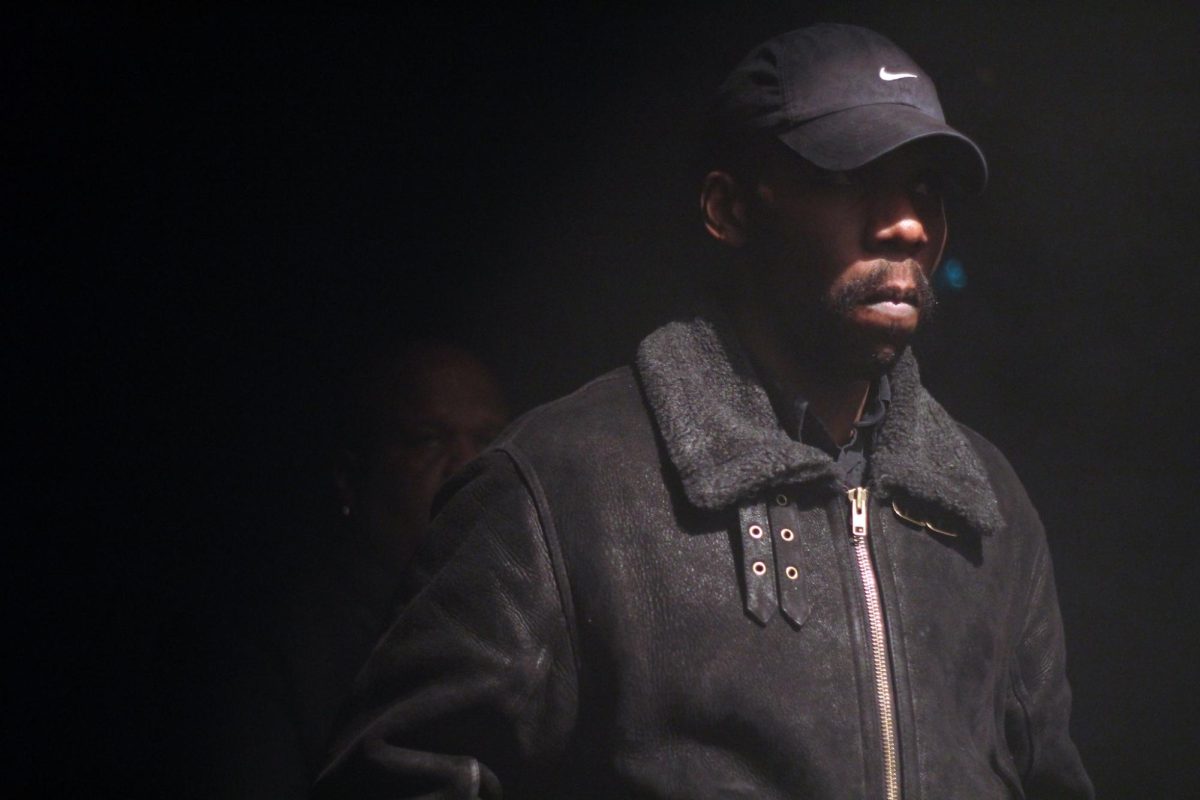

Moreover, audience members were able to observe characters on an individual level, and watch as many of them dismissed or rationalized each others’ points of view. Doremus’s affair with the likeminded Lorinda Pike (Carla Befera) kept the character from being depicted as the image of moral goodness and perfection, as did his disdain for his “hired man” Shad (Jorge Diaz); when Shad revealed to his employer that he was planning to vote for Windrip, Doremus Jessup doubted his literacy in a pitiful tone.

Pascal, the performance’s resident Marxist, proclaimed to him, “Patience is something that only bourgeois liberals can afford”, critiquing Doremus’s privilege as an educated, middle-class man as a reason for his insistence on painstaking negotiations rather than drastic revolution. The editor’s own son Philip (Richard Hornor) credited those who voted for Windrip with “want[ing] a voice…want[ing] agency over their lives”, sparking a family feud. Despite Jessup’s role as the protagonist, he was nonetheless out of touch with an entire population by way of status, education, and class — an issue all too common in today’s spheres of politics and activism.

In the play’s second act, a picture is painted of the United States devolved into military rule, Windrip having been deposed. Journalism had been forced underground, and Doremus and others had been sent to concentration camps for their publications. The shift from a familiar society to a totalitarian one felt quick and odd — prison guards wore SWAT vests, inmates orange jumpsuits, and by the closing scene, Sissy Jessup (Alexis Standridge) was posting some variety of anti-government propaganda from an early-2000s MacBook. Act two seemed slightly contrived — the lines between the “bad guys” and the “good guys” had been distinctly drawn where they had once been ambiguous, and the military antagonists seemed to lack much depth — save for Shad, who reveled in his new authority and dominance over Doremus before being sent to a camp himself.

That said, it’s entirely possible that this second half simply seemed more fantastical to me, as it isn’t a situation that I’ve lived through — unlike much of the first act.

In spite of this, the show closed with an important thought: a member of the ensemble insisted that in both the lead-up and aftermath of Windrip’s election, “most people were too busy trying to survive to do any complicated thinking.” A girl in Canada, learning from Doreman about political theory and activism following his escape from the United States, reaffirms this idea: “you let your brain go slack, and it hurts when you start to use it again.” Above all, It Can’t Happen Here shows us the turmoil that ensues when we allow emotions to entire commandeer our fiction; director Bruce McLeod instead encourages us to “pay attention…talk, don’t yell…[and] listen and engage.”

“It Can’t Happen Here” plays at Lohman Theatre at Foothill College from November 2nd to November 19th, 2017, Thursdays through Sundays. More information can be found at www.foothill.edu/theatre.

All photos by David Allen: http://www.cb-pr.com/press/itcanthappenhere.html

Bruce McLeod

Nov 10, 2017 at 10:23 am

Alix,

What a tremendous piece of writing. Thank you for your insights and time as well as your encouraging words about the play and the production.

Most of all, thank you for appreciating the impact of live theatre.

Bruce