The Mental Health Crisis: How neglect mass-manufactures mass-shooters

“He sends his mom cookies. There’s nothing else to say … I would love to be able to give some reason for this.” These words by Eric Paddock, brother of the gunman who claimed 60 lives and injured 500 more yesterday, reflect the known, yet vastly ignored problem of mental health in our country.

The attack came as a shock to the gunman’s family; bewildered and grieving, they described him as “just a guy who lived in a house in Mesquite, drove down and gambled in Las Vegas. He did…stuff, [ate] burritos.” The question arises of how such a vile attack could have been planned and executed without notice, even by the man’s family.

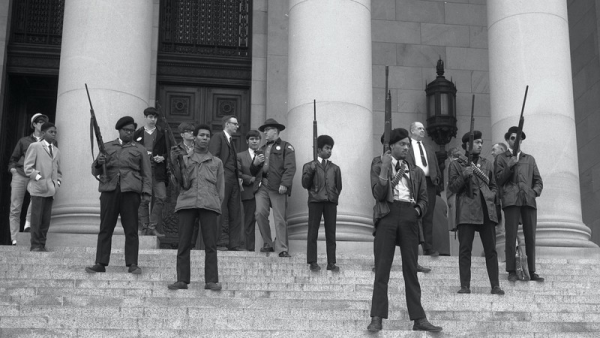

Throughout America’s long history of gun violence, debates and discussions of all character repeat in seemingly endless cycles: Should we be more strict on gun-control? Were the guns illegal? How did the President respond? Who are the victims? Who was he working with? What does the family say?

In the days following a mass shooting, the public will jump to investigate these questions, politicians will take minutes of silence to offer their “thoughts and prayers”, and then soon, the conversation will be forgotten, until the next time.

Though the debate around increasing gun control is important to support, ignoring the topic of mental health and mental health reform is an egregious mistake. How is it that “just a guy who eats burritos” could mastermind and carry out the largest mass shooting in modern U.S. history without intervention or even the slightest warning of danger from those around him?

According to reports, 60% of perpetrators in mass shootings since 1970 “displayed symptoms including acute paranoia, delusions, and depression before committing their crimes.” It is true that they are often socially isolated, unstable, and deviant from what we consider social norms — Jared Loughner’s classmates felt uncomfortable around him before he shot Congresswoman Giffords and 6 others when “he would laugh randomly and loudly at nonevents” in class, and Virginia Tech shooter Seuing Hui Cho was admitted to a psychiatric hospital when his roommate expressed concern over his mental health. Nonetheless, it is wrong to attribute gun violence as an inevitable consequence of a mental disorder.

When conservative commentator Ann Coulter famously proclaimed that “Guns don’t kill people, the mentally ill do”, she overlooked one issue.

When entire families, retirement homes, and workplaces are shocked that a member of their community develops such a meticulous and extreme plan — Paddock was said to have 19 rifles, 2 machine guns, and over 100 rounds of ammunition in his hotel room — to rob hundreds of lives before turning the trigger on themself, there is no doubt that a mental health issue was being left unnoticed and untreated.

This is not to say that individuals experiencing mental illness are more likely to be violent or commit crimes. In fact, mentally ill people only make up a small fraction of gun homicides in the United States. The issue at hand is that, though small in comparison to all gun homicides in the United States, the number of “lone wolves” or “normal guys” (as Paddock’s neighbor described him) that commit mass shootings, violence, or terrorism is disproportionately high.

Not all mass shootings are committed by mentally ill people, and not all mentally ill people become mass murders. However, there is a high correlation between the two and a vacuum of support to leave these individuals to their own devices. By further stigmatizing mental health by assigning blame to the “deranged lone gunman”, we are only making it harder for them and their families to seek help.

We will never know for sure, but it is highly likely that by changing the narrative around mental health and making access to support networks and treatment widely available, less burdensome, and more socially acceptable, individuals like Paddock could have received help before a shower of bullets flew over the Las Vegas strip.

Like the bystander who helped intervene in Jared Loughner’s assassination attempt and mass shooting testified in court, “That beautiful day, our mental-health system failed us.”

And it still does.