International Education Week: A Native Perspective on Climate Change

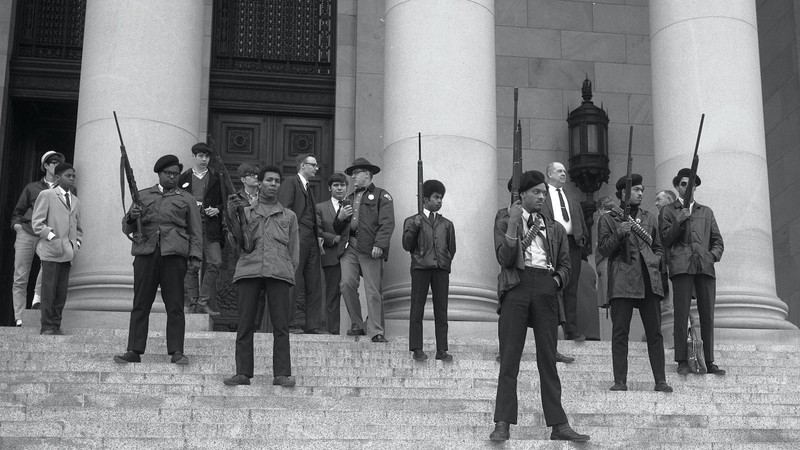

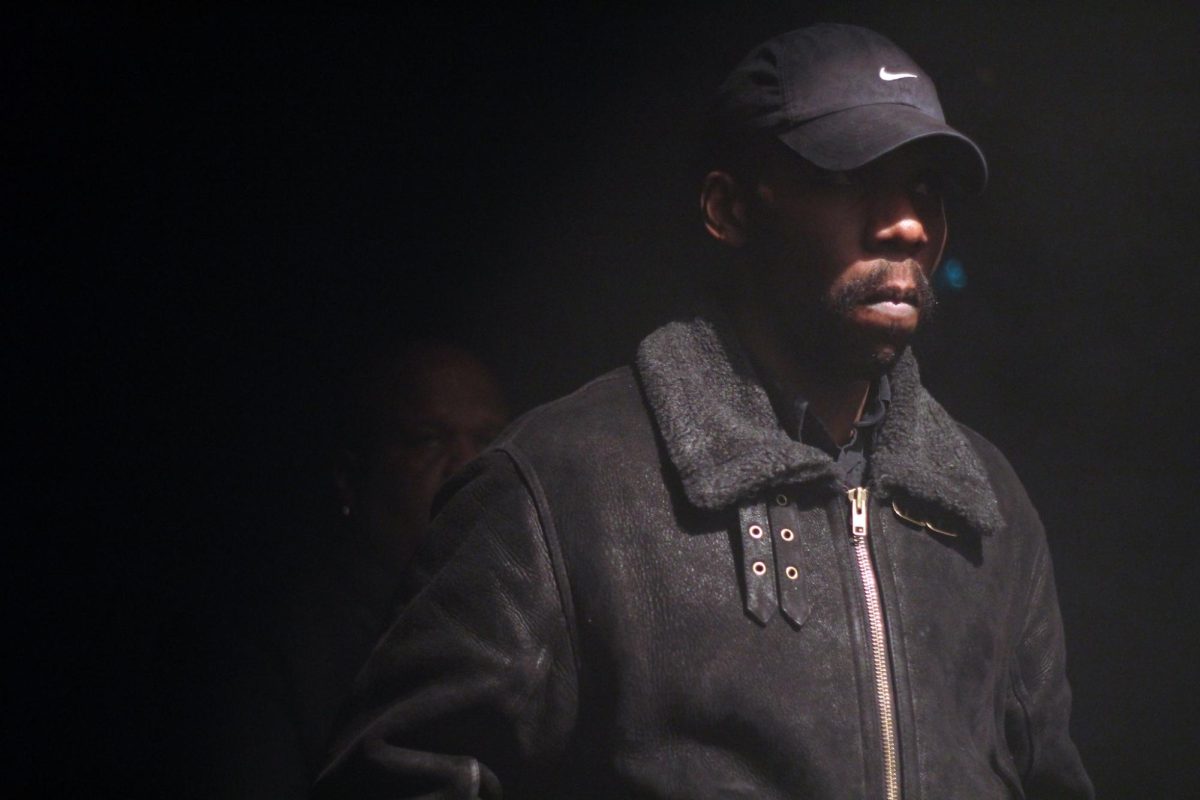

The Standing Rock Reservation camp in December 2016

“My grandfather was brought to boarding schools run by missionaries…they killed the Indian but kept the man,” Rochelle Diver described of her family’s history in the United States.

Diver spoke to Foothill College students on Tuesday in the Hearthside Lounge, as part of International Education Week, co-sponsored by Native American Heritage Month and Foothill’s Associated Students. In her presentation, she discussed her own family history, her role as part of the International Indian Treaty Council, and the importance of environmentalism to Indian American communities.

Diver is a member of the Fond du Lac tribal community, one of six Chippewa bands in Minnesota. Her grandfather’s story isn’t atypical — Native Americans across the nation have been targeted by oppressive policies, such as the Indian Child Welfare Act and the Indian Removal Act, for decades.

Reversing their effects, and ensuring such human rights violations never happen again is one of Diver’s goals as director of the San Francisco office of the International Indian Treaty Council. Her job includes executing IITC programs such as the The Indigenous Women’s Environmental and Reproductive Health Initiative, negotiating multinational treaties at various conferences, and educating others about indigenous people’s issues and rights.

The International Indian Treaty Council was founded in 1974 to recognize and protect the rights, land, and sovereignty of indigenous peoples worldwide. The organization began lobbying the United Nations to adopt the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People in 1977 — the United Nations obliged thirty long years later in 2007, and the Council was given general consultative status.

The Council was then able to negotiate treaties, but couldn’t vote on them for lack of nationhood. Still, it is the “most comprehensive international instrument on the rights of indigenous peoples”, and has garnered support from all 188 countries in the United Nations, though America originally voted against it.

Despite these milestones, Native Americans still disproportionately carry the burden of environmental degradation, Diver pointed out. Native Americans practice sustenance living, and that tradition is threatened by pollution of land and population declines of animals such as seals and whales. In Northern California, Diver described, aerial pesticide sprayers often spray pesticides upon neighboring indigenous lands and populations while spraying crops. The concentration is sometimes so high that girls carrying tulle in their mouths for basket weaving develop mouth cancer.

For a community as closely tied to the environment as Native Americans, a healthy environment is the only guarantee of health and survival. And according to Diver, that’s where the modern day fight for human rights for all, especially Native Americans, should be.