Review: “Indelible India” Photography at Foothill’s KCI

What defines a nation? A quick Google search presents all the biggest ways in which America and India differ: by population, industry, and government. Though helpful to some, such knowledge may paradoxically misinform those curious, and cause them to project what they know of other countries that similarly differ from America onto their perception of India. The Indelible India photo exhibit aims to close this gap by presenting “images of daily life in Northern India” against the backdrop of some of India’s most historic and religious cities, such as Delhi, Agra, Varanasi, Jodhpur, and Jaipur. Being from, and having visited Northern India myself, I was curious to see how those who had never been India would experience the country, and if they could do an accurate job representing it.

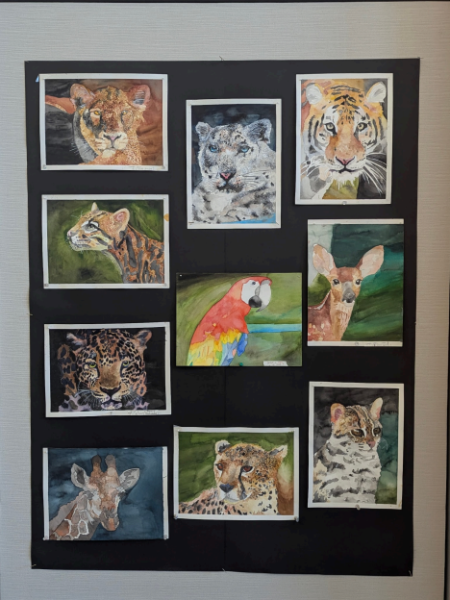

The exhibit consists of 30 framed prints, most of different sizes, placed side by side in the KCI’s half dome viewing gallery. The content of the photos is as diverse as India itself. Photos pull from both classic Indian scenes, such as the shore of the Ganges River at Varanasi, to mundanities such as a bicycling man, expressing the mannerisms, poverty, religion and public-facing nature of India. Details such as the composition, editing style, and presentation of photos make the exhibit a strikingly immersive experience.

Sheryl Guiao

Sheryl Guiao

Upon first glance, the diverse contents of each photo seem to confuse each other, as well as the viewer. A picture of degenerated Hindu posters in an equally decayed room is right before the pristine interiors of the Taj Mahal, still a Muslim mosque today. A photo of beggars on the street comes before the majestic Great Wall of Amer. One might see the aforementioned photos and ponder what it means to be religious, or consider what life is like in places we, as tourists, take only at their face values. The gallery relies on the individuality of each picture to strike the viewer and place them in a certain mindset. Then, with its adjacent photos, it builds on this mindset to convey some sort of meaning — one that is up to the viewer’s now somewhat informed interpretation.

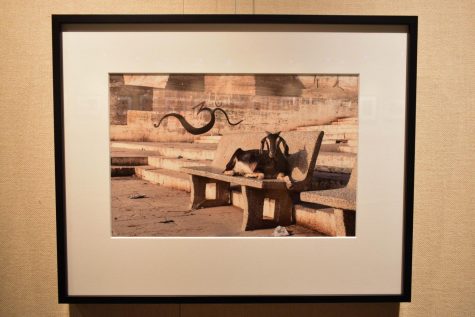

Of course, the above effect of the collection is possible only thanks to the composition of individual photos in the exhibit, which allow each to serve its own purpose. I was particularly impressed by Wheatley’s “Ghat Goat,” in which a goat is sitting on a bench in a public setting, with the sacred Hindu symbol Om on a wall in the background. Any photographer could easily read that Om is a sacred symbol to India’s 80% Hindu population, and easily find one to photograph alone. Wheatley’s rendition of this ubiquitous symbol presents it in a way that asks the reader to consider the role religion plays in India, especially locally. This same photo hints at a relationship between Indians and the many roaming animals that cohabit their streets.

Kathy Honcharuk

Kathy Honcharuk

The editing of the photographs is generally fairly subtle, but aids the viewer in understanding what they would feel had they been in the position of the photographer. A particularly well done example is Michael Collins’s “Street.” The picture is slightly sharpened, emphasizing the debris on a beggar’s face and all around, the worn down quality of material items such as the wagon and bag. Other times, the decision not to edit is the best one. Kate Winn-Rodger’s “Yogi” allows heavy daylight to do the trick. The shadows on the yogi’s face aren’t glamorous, but neither is practicing religion in 90 degree weather, as so many in India willingly do.

The photographers of Indelible India examine India at eye level with Indian people themselves, rather than project their preconceptions of the county on their work. Indelible India is a testament to the power of cultural relativism in photography, and the power of photography as a perhaps the best means of understanding a country.