#TakeAKnee: Legality vs Morality

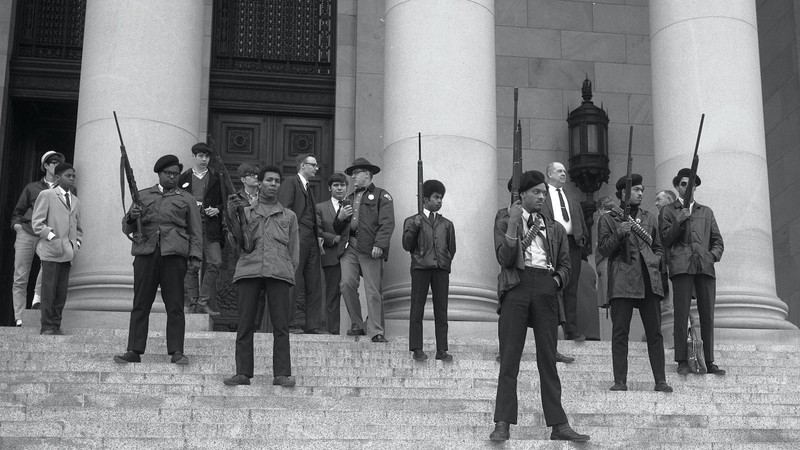

Last Sunday, October 8th, Vice President Mike Pence exited the 49ers-Colts game prematurely, following twelve 49ers players kneeling in protest during the National Anthem. This form of protest has incited controversy since Colin Kaepernick, previously of the 49ers, popularized it when he began to sit, then to take a knee, for the duration of the National Anthem throughout the NFL’s 2016 preseason. In the wake of the election of President Trump, the protest has garnered even more support from athletes of all colors which has incited further discontentment from those who consider it offensive. Those opposed, including Trump, tout the uncompromising importance of respecting the flag, the military, and the United States by standing during the anthem; Kaepernick, on the other hand, has expressed his discomfort in showing unqualified support for a country seemingly tolerant of the frequent incidents of police brutality committed against African Americans. While the protest is entirely legal, the debate over behavior during the National Anthem is yet another arena of conflict between two opposing groups with different contexts for their patriotism, and it exemplifies an overall failure to see past party and racial lines.

The first thing to consider when joining or analyzing this argument is whether to approach it from a moral, or a legal standpoint. If one opposed to Kaepernick’s form of protest made the decision to bring protesters to court, the plaintiff would be severely disappointed: those who choose to kneel are in no way violating federal law. Most obviously, the First Amendment grants all people the rights to speech, expression, and assembly. Furthermore, the US Supreme Court previously established specific precedent for cases in which citizens choose not to pay respects to the flag in Minersville School District v. Board of Education, in which two young Jehovah’s Witnesses refused to salute the flag during the pledge of allegiance during class for religious reasons. While originally it was ruled that there was no reason the school couldn’t “…revoke and foster a sentiment of national unity among the children in the public schools,” the ruling was reversed in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. In this case, Justice Jackson proclaimed that “compulsion as here employed is not a permissible means of achieving ‘national unity,’” prohibiting the court from mandating that the children stand and salute the flag.

The one document that does buoy the main argument of those who oppose these protests is the United States Code, first published in 1926, which reads that during the national anthem, “all…present should stand at attention facing the flag.” However, both the use of the conditional tense and the failure to include any consequences for noncompliance suggests the clause is more of a congressionally-approved formality than an enforceable law.

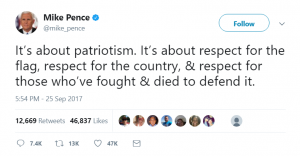

Legally speaking, those who choose to kneel during the anthem, like Kaepernick, are doing nothing wrong. The moral argument against them is more complex though: those who find the NFL protests offensive proport that they disrespect the United States of America itself, veterans, military, and those who have fought and died for this country. Prior to his pre-planned exit from Indianapolis on Sunday, Vice President Pence tweeted, “It’s about patriotism. It’s about respect for the flag, respect for the country, & respect for those who’ve fought & died to defend it.” Tomi Lahren, conservative contributor at Fox News known for her incendiary Facebook videos, also criticised the protesters, tweeting, “How about these whiny football players go to a local VFW and ask true heroes what that flag, service and sacrifice mean?” Initially, these comments, and others like them, seem severe, but with context, one can get a better picture of the logic of those who oppose kneeling. Pence has a son who is an active duty marine; Lahren’s grandfather was a World War II paratrooper, her uncle a Vietnam purple heart recipient. Those with similar opinions to Lahren and Pence have generally grown up valuing military service, and hold the belief that the anthem and flag of the United States are synonymous with the efforts of service members close to them.

Like Lahren and Pence, Kaepernick’s position comes from a belief rooted in compassion: regarding his failure to rise for the anthem, he stated, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color.” According to the Washington Post database, thirty-four percent of unarmed men who were shot in 2016 were black, displaying the vastly disproportionate violence a group that makes up only six percent of the US population experiences. In response to this violence, Kaepernick kneels with the intent to draw awareness to the brutality black Americans have seen for decades but white America has only just noticed. Following criticism Kaepernick reaffirmed the subject of his protest as police brutality, making it clear that he holds respect for veterans, but this comment assuaged few critics. Today, whether a player stands or kneels is interpreted as a measure of their love for America, opinion of the Trump administration, or respect for the Armed Forces, but the origins of the recently popularized movement have been lost under the din of cacophonous inflammatory tweets. Morality aside, Kaepernick’s methods are successful so long as his actions incite debate about America in the context of black lives.

Both staunch supporters and rigid opposers of kneeling during the national anthem share strong emotional conviction for their causes. On one hand, a group touts the importance of national unity under the symbol of the flag. On the other, this peaceful protest raises awareness of the brutalization of a group historically oppressed under that same symbol. The current situation echoes what Frederick Douglass delineates in his famous Fourth of July speech:

“To [the American slave], your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

Douglass expresses the ironies in the sentiment of freedom through overwhelming patriotism that is expressed in the US on fourth of July to an entire population enslaved; Kaepernick expresses his distrust of a flag and anthem that establishes “liberty and justice for all” as a key American tenet, but fails to recognize that it has yet to be achieved. Those opposed to Kaepernick are either incapable of seeing his point of view, or understand yet prioritize their view of the Anthem and Flag, as a means to convey their respect, over his. Ultimately, the conflict over what it means to stand for the National Anthem boils down to an idea expressed by Justice Jackson in the West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette case: “A person gets from a symbol the meaning he puts into it, and what is one man’s comfort and inspiration is another’s jest and scorn.”

Until we as a nation can recognize that the diversity of experience in American culture is accompanied by a diversity of thought that shapes the way we see our country and ourselves as citizens, we will continue to struggle over the true meaning and expression of American citizenship; despite the fact that there may well be more than one right answer.