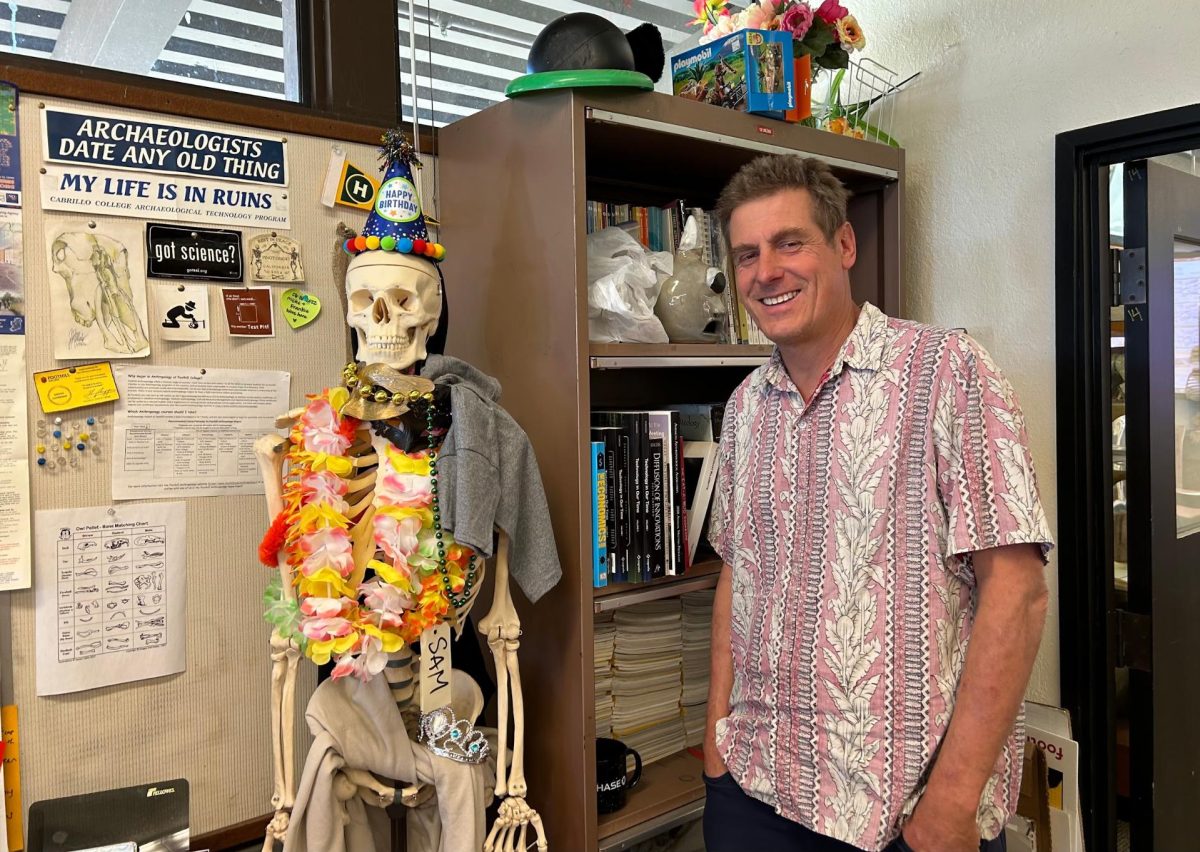

Jeff Anderson.

If you’ve been at Foothill for even a few quarters, you’ve likely heard of this name. If you polled students about him, the kinds of responses you might get would be incredibly distinct.

“Best Professor I’ve ever had!”

“Kind of a hardass, but it’s an easy A if you do the work.”

“Transformed my outlook on education, and my time in his class is irreplaceable.”

“Wants you to do a bunch of unrelated BS. He’ll pester you about it, but you can just skip it.”

“Taking the time to do meaningful work in his class made my other classes less stressful.”

Jeff himself is as varied and multi-faceted as the opinions of him among the student body are.

His decision to become a teacher was only set in stone in his mid-20s, but the story doesn’t start with a tidy origin tale or a sentimental memory of his “favorite math teacher.” It starts with data. It starts with outrage. And it starts with a choice: one that many in academia don’t make.

“I was deciding between Goldman Sachs, Google, and teaching,” he tells me, casually describing paths to multi-billion-dollar corporations. “But by 2010, in graduate school, I had pretty much signed in blood that I would be a teacher.”

Jeff doesn’t see the status quo in our modern college system as politically neutral. Quoting the book Talking about Leaving Revisited, Jeff explains that a large collection of research-based evidence documents the reality that most colleges routinely weed out 60% of declared STEM majors before graduation. Jeff says: “I expect better from myself as a professional than 40% success rates in my classes and college. What would we say about an automotive industry that designs cars that kill more than 60% of drivers due to engineering decisions, not driver error? I believe we can and should do better than that. Our students deserve better and so does our society.”

Jeff is careful to say that he does not blame individual teachers, staff members, administrators, or colleges for this problem. Instead, Jeff wants to be part of a larger team of people who learn to analyze this hurtful status quo by naming the harm encoded in current teaching and governmental policies. Jeff says that “once we learn how to name the harm and understand where that damage comes from, let’s work together to figure out how to transform our approach to education to shift the focus away from wealth extraction towards authentic student learning.”

To help him visualize the structure behind the status quo, Jeff created a diagram that highlights component pieces that form the foundation of our educational reality, as seen below.

Jeff reports that “in my work as a teacher and content creator, I spend tons of time re-designing my approaches to curriculum, learning activities, and assessment policies to focus on student learning. In this effort, I want to specifically identify research-based models for learning that can inform my decisions, empower students to create excellent educational learning experiences, and protect students against harmful policies that are designed to uphold wealth supremacy.”

The Ungrading Journey

Jeff’s take on assessment isn’t just radical—it’s existential. “What is learning?” he asks his students. “Give me a research-based definition. If you can’t define what learning is, how do you assess it?”

For years, Jeff operated within traditional grading systems. Under the mentorship of Foothill math professor Nicole Gray and following the model created by Foothill’s MathMyWay program, he built multiple versions of exams, gave students chances to redo assignments, and often worked 50- to 80-hour weeks to ensure everyone had a fair shot. His end-of-term success rates climbed. What was once 60% grew to 70% and then 80%. Jeff was excited, ecstatic even, as it continued to climb.

However, more quarters passed, and that success rate plateaued. No matter what Jeff tried or how many hours per week he put in, while working with each student to the best of his ability, his success rates never went past 80%. Most teachers would have been content with that. An 80% passing rate in college STEM classes is above average and reflects what most teachers might consider to be good teaching.

But that continued 80% passing rate, without further improvement, didn’t bring Jeff any more joy, only frustration and hours of fruitless effort.

“…I wasn’t satisfied because, if my success rates are 80% percent, that means two out of ten students in my classes are failing. And for those two students, what happens when I fail them? If I’m being honest, I must realize that some of those students give up on their education and go away forever. That is a heavy burden that rests on my shoulders as a teacher.”

Jeff has often described his “scrapper’s attitude” where he tells himself that “whatever I put my mind to, I will accomplish. The only way I won’t accomplish something I care about is if I die before I finish.” With a single-mindedness that did no favors to his health, he tackled his research regarding assessment again and again, but nothing worked. It was only through a conversation with Patrick Morriss, another Mathematics Professor at Foothill College, that Jeff was able to make a breakthrough.

Jeff had attended some talks that Mr. Patrick had given at state-wide and national conferences. However, Jeff describes that he “wasn’t ready to receive” the knowledge that Mr. Patrick was imparting yet. It was only after over a year of struggling with 80% percent success rates and no progress that Jeff was in a place where he could finally listen. Jeff describes how he found himself in a dialogue with Patrick about this struggle to help students learn deeply without requiring failure.

“I said to Patrick: ‘I can’t keep up this pace and I can’t seem to exceed 80% pass-rates…I feel like I’m hooked on a drug and I just can’t kick the drug, Patrick. I’m worried that this is the best I’ll ever be able to do in my career, and it breaks my heart because there is a real human impact to those 20% who fail. I just don’t think I can do it.”

Morris’s response?

“Sure you can, dude.”

What Jeff heard?

“You aren’t asking the right questions. You need to think deeply.”

And Jeff did. He read 90 books. Hundreds of research articles. He went from being “a teacher who grades compassionately” to someone who saw the system of letter grades itself as the poison. “Our letter grading systems don’t just fail students. Grades lie to students and teachers. Grades tell a student who had every advantage in the world that their A is evidence of effort rather than an indication of privilege. Grades tell a working student, a homeless student, that their C is a moral failure. Grades tell teachers that punishments and rewards are good tools to influence student learning despite the fact that we have 100+ years of scientific evidence that documents the exact opposite: that letter grades harm learning and actively block teachers from helping their students to learn deeply.”

Inspired, Jeff made a sharp turn: he stopped using grades to guide learning.

But his “ungrading” approach isn’t some free-for-all. Students write reflective letters at the end of the course, determining their own final grade based on transparent, research-driven criteria. They justify their learning with evidence.

“Grades do to student learning what cigarettes do to the human body,” Jeff explains, quoting decades of educational research. “Letter grades are toxic. They cause harm. But nobody questions our grading system, because we’ve all been raised to see letter grades as necessary.”

Jeff’s ungrading system challenges that logic, and while it sometimes invites resistance from colleagues and students alike, it offers something else, too: agency.

A Textbook For All

Jeff is currently writing an applied linear algebra textbook that he hopes will make all other linear algebra textbooks obsolete for students, at least in terms of how they can learn deeply. He plans to release the book, complete with fully worked-out solutions and 3Blue1Brown-style videos, for free. And he’s not doing it alone: he’s finding ways to pay students to help him write the solutions. “Math takes time,” he says. “And a lot of students don’t have time because they’re working or dealing with the financial pressures of life. So I raise money to pay them.”

It might come as a surprise to learn that Jeff did not originally intend to include in-depth solutions to undergraduate-level exercises as part of his textbook project. When asked what made him change his mind about this, he responds simply, “Because students told me they wanted it. I asked my students if they preferred just the textbook or if I should also include fully typeset and well-written solution sets alongside the exposition. Students overwhelmingly voted that I should not only provide a good textbook but also provide open-access solutions so they can check their work. As a mathematician, I know that our national math Olympiad teams routinely provide top-level mathletes with full solution sets to expedite their training routines. I saw in my students’ request that students yearn for timely corrective feedback on their problem sets to deepen their learning. I love listening to my students and I am so happy to change my approach to respond to student requests.”

In addition to finding grant money to help pay students for the time they spend, Jeff also funds these efforts with his own money and outside consulting work. At present, every cent of his YouTube and Patreon income goes into a separate content-creation account designed to support students and build an excellent open-access curriculum. “None of it goes to me. I don’t touch it. It all goes to my students.”

The vision? A world where no student is forced to pay $150 for a textbook written by a Stanford professor who’s never taught at a community college.

“Those books weren’t written for students,” Jeff says. “They were written for teachers. The only reason they sell is because teachers require them.”

His mission isn’t just educational. It’s also economic. “Wealth extraction is when money is taken from local communities and sent to far-off corporations,” he explains. “I want to do the opposite. I want to channel money from big institutions to support student learning in local spaces.”

The Paradox of Popularity

Jeff Anderson’s classes are among the fastest to fill at Foothill. Within hours, and sometimes minutes, of enrollment opening students find that the slots are gone and the waitlist is overflowing.

During my time in two of Jeff’s classes over the last year, I observed what I perceived was many students who disengaged or underestimated what they’ve signed up for. When I pose my conjecture about this phenomenon, I expect to see Jeff nod along, with perhaps a sigh in shared frustration. Instead, he pushes back, empathy for something I hadn’t considered shining in his eyes.

“I would actually challenge the disengagement thing. And this is something that gets into what models of learning we use to guide our decisions in our system. When we interpret absences or low performance as disengagement, I think it gives our school system a free pass. That mis-belief allows us to avoid hard work.”

Jeff goes on to describe what he expects of his students and holds his students accountable for, that being their learning. He is careful to delineate deep learning from shallow learning.

“Just because I get a right answer on exams or submit work that satisfies my teacher, does that mean I am fully engaged in that effort for my own purposes? How often do students feign learning in school while treating teacher expectations as surface-level check lists to be completed and then forgotten? How often do students finish a class without making significant and personally meaningful changes in their knowledge, beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes? When I work with my students, I want to help them engage in deep learning that they believe is important and meaningful. This is always hard and sometimes my approach to teaching challenges students in ways that they aren’t prepared for. The resulting discomfort can show up as absences during in-class meetings. But the cool thing about my approach to teaching is that I ask my students to look at me in my eyes and tell me what is going on for them. And they can’t get through my class without providing me evidence, via dialogue, that they are making significant changes in their content knowledge and creating powerful meta-learning strategies.”

More than that, Jeff refuses to place blame on his students. In a system that rewards and encourages apathy and distance, he refuses to be passive.

“In my dialogue with students, students tell me stories about homelessness, about rape, about domestic abuse, about suicide. I ask my students, with genuine curiosity and interest: ‘what’s going on that is blocking you’re learning?’ Then I am amazed at what I hear. And, you know what kills me? Nobody asks what kind of work a teacher would have to do to build this type of trust with their students. Instead, I get asked ‘Why are you talking about that with your students?’ And you know what my answer to that is? I ask my students to show up authentically, as they are. I promise my students that I will do my best to celebrate their identity and find ways to help them build teams to support their learning. I believe, as a teacher, that if I can’t celebrate a student for their full humanity and the depth of their life experiences, how am I supposed to teach them? If a student is struggling with suicide, do you think that the solution to that is to give them more linear algebra? The most important thing I can do for that student is support them in getting help and show genuine care for their well-being. Then the statement is, when that student gets the help they need, should I use my power as a teacher to force them to comply to an arbitrary 12-week quarter? I believe our students deserve better than this: they deserve patience, grace, and empathy. So, I don’t see the disengagement. I do see the underestimation, but I don’t blame my students for that.”

Visibly emotional, Jeff ends with his advice to students interested in his class. “Show up as you are. Read every word of the welcome email. Do things that you believe matter for you. Take responsibility. And let’s have some fun together while getting you ready to thrive as you build your dreams and strengthen your learning skills.”

2BL: Where Math Meets Meaning

It’s hard to explain 2BL, Jeff’s experimental Linear Algebra Lab course, without feeling like you’re describing something from the future.

There’s no textbook. No set list of topics. No timed exams. Not even a list of lessons. Instead, students embark on self-guided modeling projects: tracking the weight of player decisions in a CYOA game, building models for CT scans, mapping decision-making patterns in Dungeons and Dragons creatures, creating systems for browser-based security, and so much more.

It’s math, yes. But it’s also meaning.

“The traditional approach is: here’s a formula, now apply it to this problem,” Jeff says. “But what if instead, we asked: what problem do you want to solve? And then used linear algebra to get there?”

Jeff’s goal is for students to develop what he calls an “intellectual need,” what he describes as a personal reason to want to learn the material. “When students realize they’re stuck in a project they care about, and linear algebra is the key to getting unstuck? That’s when real learning begins.”

2BL isn’t a requirement for IGETC or a Major, which is likely why enrollment lags behind his other courses. But Jeff believes the course offers something most students have never experienced: a chance to connect math with their actual lives in a meaningful way.

As a member of his 2BL course, I’ve felt that intellectual need grow in myself. I found myself going back to Lessons from the standard Math 2B course, poring over matrices, systems, and models even after I’d provided evidence for my learning and grasped the material. It wasn’t enough to just grasp it for what I wanted to accomplish; I needed to be an expert. Eventually, I saw that I wasn’t just learning math. I was using math in ways that mattered to me, and not just in the way that a teacher set out for me.

And that’s the heart that I’ve found in 2BL. Students don’t learn because they’re told to. They learn because they want to.

Jeff sees 2BL as an answer to the vacuum left behind when grades are removed. “Grades are easy. They give cheap answers to hard questions. But when you take the threat of grades off the table, students ask, ‘Why am I doing this?’ 2BL helps them find that answer.”

The Dream

Jeff has a vision for what college education could be.

This dream includes the following features:

- Students can take up to seven years to graduate if they need to.

- Financial support that covers food, housing, and learning supplies.

- Class start and end dates are determined in dialogue with students rather than an arbitrary school-centered calendar that is blind to student needs.

- Assignments have meaning and students learn at their own pace in community with each other.

- A world where grades are replaced with growth and compliance is replaced with curiosity.

He’s clear that he doesn’t have all the answers. But he does have questions, and that’s where change begins.

“In order to change the harmful status quo that is college STEM education, we need a lot more people asking much deeper and more critical questions. We need to identify that we expect more than 40% success rates in school. We expect better school funding, more support staff, higher pay for educational professionals, financial support for students, and so much more. I love engaging in dialogue about what we can do, collectively and together, to create schools that support student learning in democratic spaces rather than schools that weed out the majority of students to enforce artificial scarcity and contribute to wealth supremacy.”

In his classes, joy doesn’t look like a party, even though the party starts when you walk through the door. It looks like rigor. It looks like transparency. It looks like a student turning in a project and saying, “I did this because I wanted to, not because you made me.”

Jeff Anderson doesn’t want to be your favorite professor. He wants to be the professor who helped you become your favorite version of yourself.

Beyond the Classroom: Letters, Labor, and a New Framework for Education

Jeff has many times explained that he will not be the one to change the world, though that does not mean he will stop trying to make all the difference that he can. Instead, he puts much of his focus on equipping the next generation with a framework. He describes the last 20-plus years of his life as dedicated to creating that very framework. It’s one that he has put to record in almost every form of media that he is proficient in. Following what took Jeff Anderson over 20 years to do may seem like a big ask, but he believes that every single one of his students can do it in 5 years, all without the sleepless nights and physical/mental exhaustion that he put himself through.

“That’s impossible,” some of his students have said. “I can’t do it.”

Jeff disagrees with these claims. It is not just a hope but a belief that every student in his classes is brilliant and genius. If students really put in the work, Jeff believes “you can learn anything you want to at the highest levels you want to fly to.”

Despite this, Jeff would disagree with any sort of statement that paints him as a kind of figurehead or leader of a movement. Jeff describes that he aims to join a movement, not create one.

However, in a system that rarely encourages anyone to speak out–let alone offer alternatives–Jeff’s persistence is one that is courageous, admirable, and valuable.

In late 2024, Jeff wrote a nine-page letter to the heads of the FHDA Faculty Association–the Negotiations Team, the Officers, and the Executive Council. The subject: the upcoming 2025–2028 contract negotiation and training that could lead to the possibility of lasting transformation in local spaces.

“Cheers to our union and all the great work we do on this campus,” is how the letter opens. It’s that note of respect and perspective that Jeff never drops, even as he urges for a deeper discussion on how things could change. What follows is not a list of demands, and not even entirely a vision. It’s an invitation to open a candid dialogue.

Later in the letter, Jeff shares some of his own reasons for writing and describes his own burnout: 120 students per quarter, over 300 each year, weeks spent working 80 hours or more. He confesses to weight gain, insomnia, chest pain, and more. “Because I want to live to see my children grow up,” he writes, “I am now spending a lot more energy prioritizing my health.” But taking care of himself, he notes, often means giving his students less. And that’s a compromise he refuses to accept without a fight.

These struggles are not something that Jeff alone deals with but are mirrored in different ways among the other faculty and students on campus. Jeff goes on to share a powerful quote from a former student of his, Henry Fan, describing that “Teacher’s working conditions are student’s learning conditions.”

The letter is available publicly on his website, and if you read it, as some on campus now have, you’ll see a man trying to contribute to something bigger than himself.

“I want to be part of CA statewide labor strikes,” Jeff writes. “…all 116 Community Colleges, all 23 CSUs, all 10 UCs, and every single public K-12 school…I want to invite faculty, students, staff, administrators, and community members to walk off the job together in solidarity.”

But, Jeff is still firmly grounded in the now, despite his hopes. “…this type of organizing work requires coordination with other schools that I don’t think we are ready for yet,” he admits. “I hope to be part of a larger team of union members that focus our efforts on our local union first.”

To do that, one of Jeff’s proposals involves a scalable training system rooted in the organizing strategies of Jane McAlevey, who is a leading voice in modern labor theory. He outlines beginning, intermediate, and advanced tiers of both independent and group learning based on her work. Books. Podcasts. Collective bargaining simulations. All of it is low-floor, high-ceiling—just like the teaching methods he applies in his classes.

He doesn’t stop at internal union organizing. On his website, Jeff lays out a first draft pitch for what undergraduate education in America could look like. The current status quo is based on outdated, unexamined, and exclusionary models for what learning is and how learning works.

Jeff’s reimagined structure starts by asking questions instead of prescribing answers. What would happen if classes were built around student learning, not academic traditions? What if students could learn in college for six or seven years without stigma or financial burden? What if math became a tool for liberation instead of a method for hoarding privilege?

He is careful, even in boldness.

“I’m not saying that I have all the answers,” Jeff said during the interview. “But I am committed to asking better questions and working hard to build answers with my students and our larger communities.”

This humility comes through not just in interviews, but in how he acknowledges those who have pushed him forward. On his website, he routinely thanks students who challenge his thinking, enshrining them in a “Wall of Fame.”

“Everything I build is co-built,” he says. “I’m not doing this alone. I can’t do this alone.”

That’s why his union letter isn’t just a request for change. It’s an invitation to co-create.

In the letter, Jeff proposes a faculty-wide book club where small groups would read one of Jane McAlevey’s books. He urges participation from executive members, adjuncts, equity officers, and even students. He suggests training cohorts that can eventually lead to campus-wide initiatives and, ultimately, broader coalitions.

And yet, Jeff’s vision is deeply personal. He speaks of lost colleagues, mentioning one of his mentors by the name of Ion Georgiou, who died of a heart attack in his office, days after confessing how unsustainable his workload was. He details heartbreaking conversations with students struggling to survive—emotionally, financially, academically—inside a system that was never built for them.

Jeff’s dream for education isn’t shiny. It’s not sleek. It’s not a Silicon Valley pitch deck or a TED Talk slogan. It’s slow. It’s built. It’s lived.

It looks like non-stop dialogue with students from the moment he gets to campus until the moment he leaves for home. Like a book club in a conference room at 6 p.m. on a Tuesday. Like a shared Google Doc with ten co-authors. Like a conversation between a student and a professor, not about grades, but about learning, meaning, and dreaming.

And most of all, it looks like a question.

What would it take to make learning a source of liberation?

Jeff doesn’t know. Not fully.

But he isn’t waiting for someone else to speak up. He’s already started asking these types of questions and working in solidarity with our community to build our own answers.

Balsher singh

Jun 14, 2025 at 10:44 pm

Jeff Anderson empowers and helps with learning thriving

Kevina

Jun 12, 2025 at 2:50 pm

Great article, Alex. I deeply appreciate your curiosity and the way you captured this truly incredible mentor and human being. Imagining and co-creating a better future for us all can be something we do together and we need people in positions of privilege to step up. Thanks to you and Professor Jeff Anderson for this inspiration!