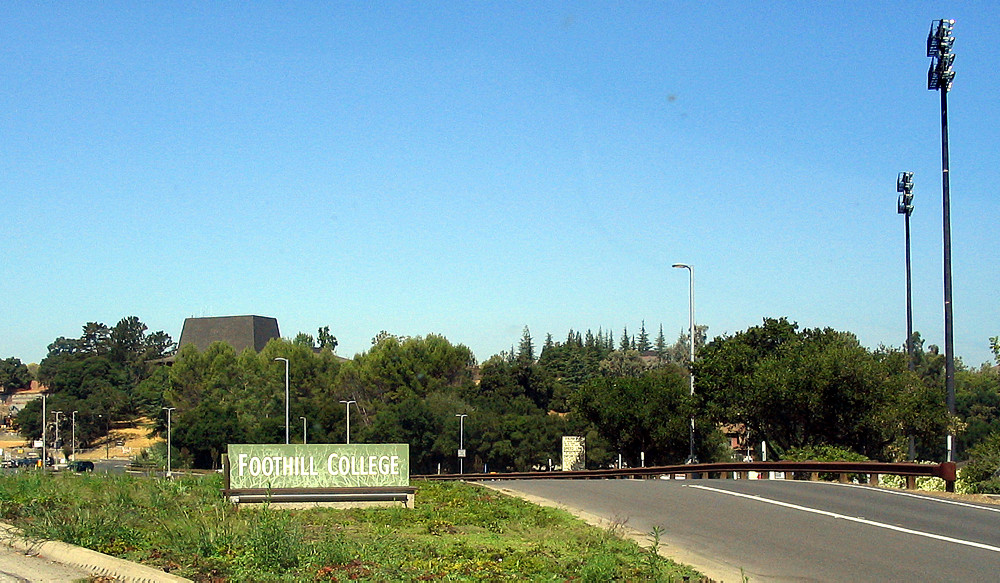

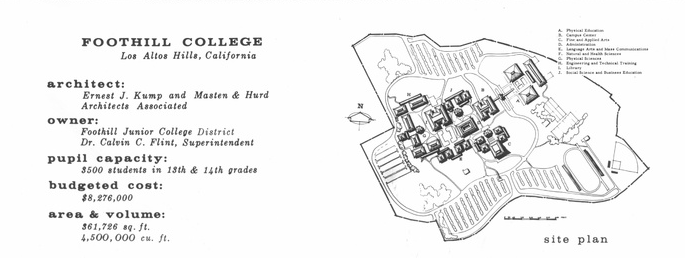

Foothill is not a traditional community college. After conquering the (literally) breathtaking staircases surrounding the campus, those of us more spatially challenged may have to pull up the campus map to figure out where, in this labyrinth, our class is. Compared to other Bay Area community colleges, Foothill stands apart. Secluded in the Los Altos hills rests the spider web of buildings, hills, benches, tables, and trees with which we are all too familiar. At its unveiling, Foothill’s unique design philosophy garnered local and international recognition, winning several architectural and design awards. But the question remains: is Foothill a confusing maze or a masterpiece?

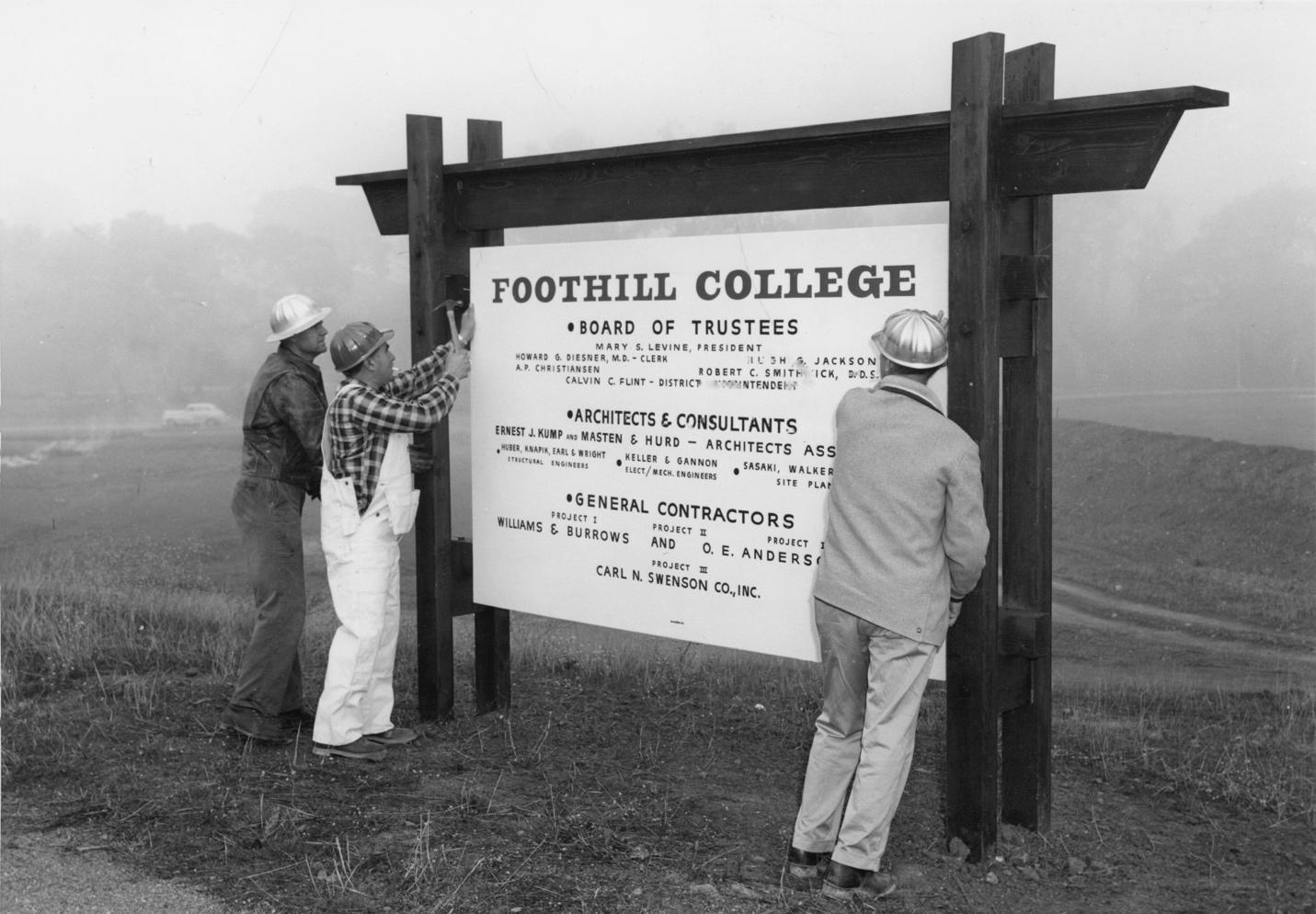

We use Foothill’s campus to learn, socialize, laugh, sleep, eat, and so much more. How we interact with our campus is driven by how it makes us feel: calm, anxious, comfortable, or awkward. The original Board of Trustees and our first president, Calvin C. Flint, understood the importance of that ‘feeling’ when they began creating a community college from scratch.

In the late 1950s, Palo Alto Unified School District leaders saw the writing on the wall: a local community college was necessary. High school attendance had skyrocketed over the last few years, and more and more jobs were requiring specialized education (25 Years Book).

In response, the Board of Trustees elected Calvin C. Flint as the first president of what would become Foothill College, the name of which only won by a single vote (Foothill Archives). His first course of action was to visit colleges across the country to find out what worked and what didn’t. He compiled his findings into a formal proposal. It was in this proposal that the importance of the latter-mentioned ‘feeling’ was made so clear.

“For reasons which may be so intangible…some campuses gave a pleasing or ‘satisfying’ effect, and others failed to have this important touch. It is this satisfying effect, this atmosphere of being an institution of higher learning, that is the architect’s responsibility.” (Foothill College Archives)

This responsibility fell to the architect Ernest J. Kump partnering with Sasaki and Walker and Associates. All were well-regarded in their respective fields at the time: Kump was a modernist architect known for school design and Sasaki and Walker’s firm was recognized for its innovative landscapes. Kump was actually fired from his own father’s architecture firm for his modernist designs; this, of course, did not slow him down (Dr. John Barton).

In 1957, just before taking on Foothill, Kump published a manifesto titled Architecture of Man in the American Institute of Architects Journal. In this paper, he described his philosophy of “true organic three-dimensional planning” and “cellular organization of organic units of space,” all of which he hoped would create an “expression of feeling.” (Architecture of Man)

I was lucky enough to sit down with Dr. John Barton to understand how spaces can make you feel. For those unaware, Dr. Barton spent years working to connect architecture and education. A former lecturer at Stanford and later the Director of their Architecture program, Dr. Barton is an expert in how educational spaces can and should feel.

“Scale, composition, and order,” he told me, “all have to play into each other…crisscross and create a web of complexity.” The successful implementation of all three concepts lends to great design.

Scale, he explained, refers to the size of elements relative to one another and the people who experience them. Composition is the arrangement of those elements in space. Order describes how they relate to one another and the spaces created henceforth. At Foothill, Barton pointed out, the covered walkways provide a clear sense of scale. The concrete columns at the edges of buildings, roughly a person’s height, are visual markers against which we can measure ourselves. Regular spacing between them, part of composition, gives the walkways a certain rhythm. The way those walkways open into transitional pavilion-like spaces creates what Barton calls pockets: the small subspaces between classrooms. The intersection of these elements everywhere on campus is how Foothill emulates that “satisfying effect” that Flint stressed was so important. It is the conversation between Kump’s philosophy and Flint’s commitment to ‘feeling’ that much of Foothill, as we know it today, came to be.

When asked what the campus’s weaknesses were, Dr. Barton mentioned two: parking and energy sustainability. “You have to have a lot of parking, and parking on hills is not great… [and] because it’s got plywood walls that are three quarters of an inch thick that are panelized…they leak energy badly. But I’m sure they’re figuring out ways to do it because it’s not optional; it’s the law.”

It’s not all bad, though. When asked what the campus’s strengths were, Dr. Barton reaffirmed how great the pavilions and landscape architecture are. Dr. Barton’s final message to students was to “turn off your phone and sit and sit in peace. Just be with the spaces because they’re so good and wonderfully scaled that you can just be there and have a conversation with a friend sitting on a bench or in the classroom. Just be there.”

This last week, I asked fellow Foothill students what their favorite spots on campus were. Many echoed similar sentiments, highlighting how nice some of the plots of grass can be on hot sunny days, the outdoor tables to get homework done or eat at, or how our library is a great place to catch up on work and run into friends. While working on this article, I became more grateful for Foothill’s grass, trees, pockets, and confusing layout.

As Dr. Barton said, and is echoed by Ernest J. Kump and Calvin C. Flint, “At the end of the day, drawings don’t tell you enough. You got to experience it.” And while Foothill may very well be a maze, it is also a masterpiece.

I’d like to thank Foothill College archivist Chris White for helping me collect sources and Dr. John Barton for generously sharing his time and insight. I’m also grateful to the students who shared their experiences and helped me understand how students use the campus today. This article would not have been possible without all of their help.