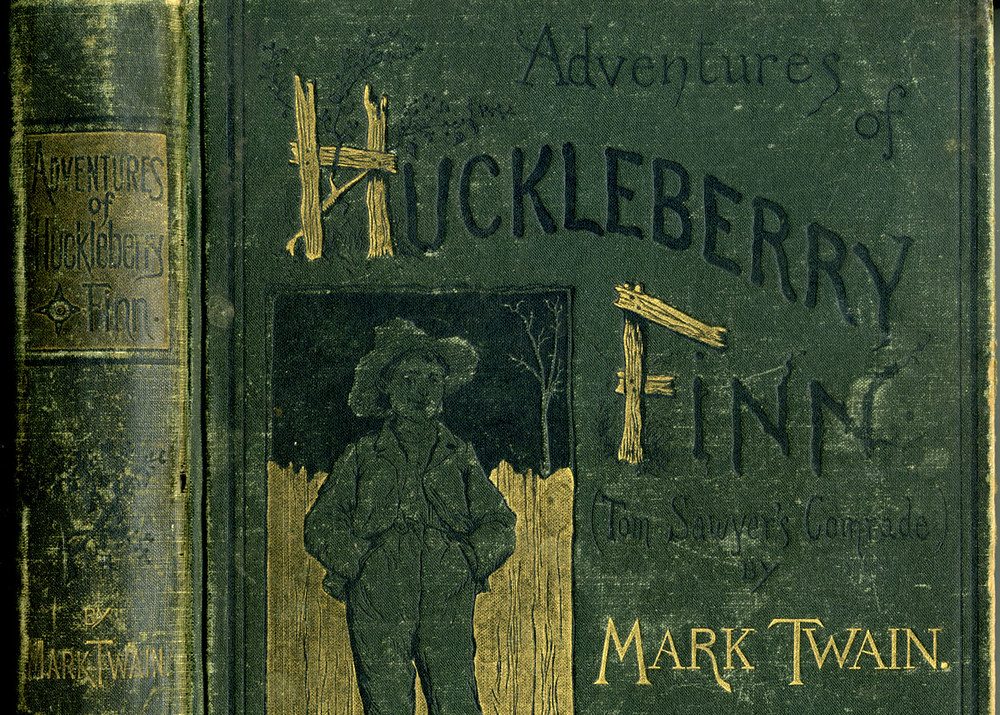

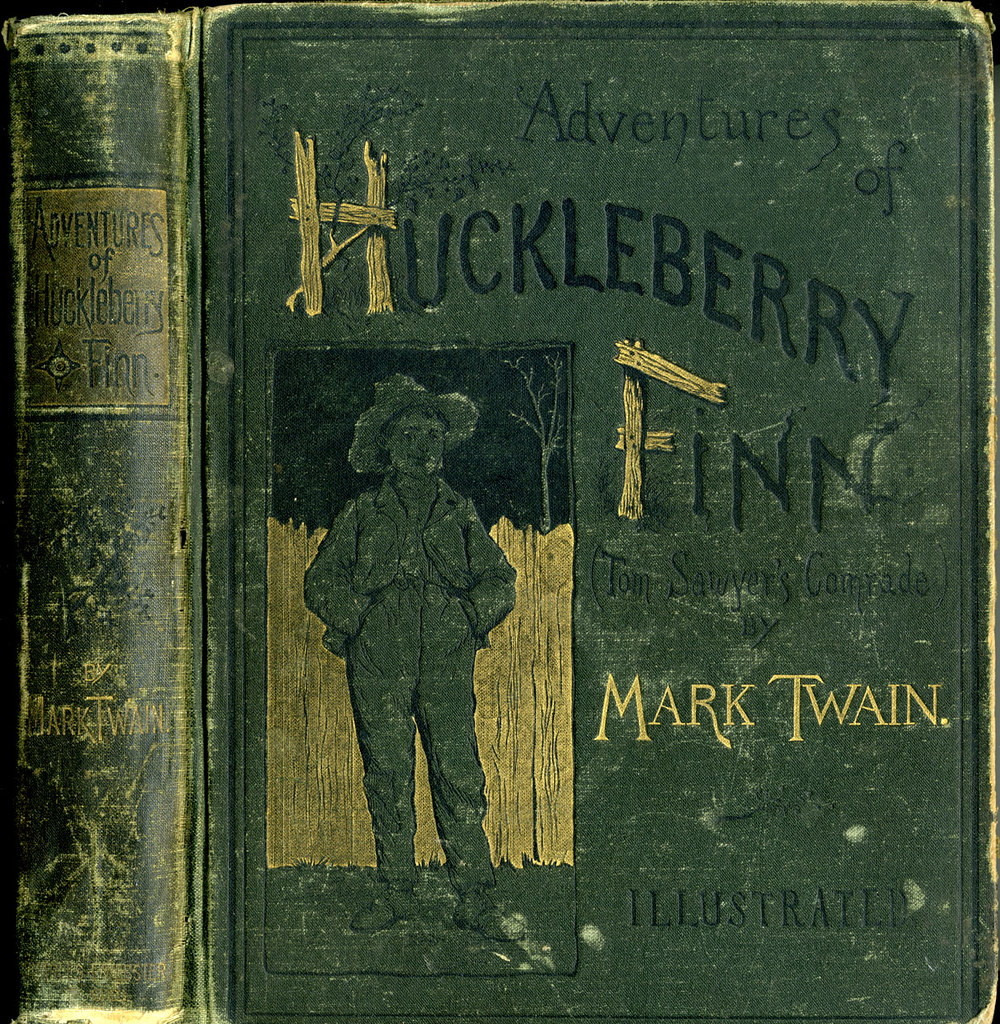

Cover of a first edition copy of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (CC by 2.0)

This October, I’ve been reflecting on an issue near and dear to my heart. As an English major and lifelong bookworm, I’ve been passionate about the consumption of literature from every genre since I’ve been able to turn a page. As a result, Banned Books Week is important to me.

Activist and librarian Judith Krug launched Banned Books Week in 1982 to combat the censorship of books in libraries and schools. The annual event takes place during late September/early October in libraries and schools across the nation, as a celebration of reading and preserving titles that are commonly censored. Often, this means books like The Hate U Give or All Boys Aren’t Blue are pulled from shelves and put on display — that is to say, books that discuss topics of gender, sexuality, or race, which, in deep red states, are often deemed unsuitable for children.

It was never difficult for me to get behind Krug’s mission. As a young queer reader growing up in rural New Hampshire, I experienced firsthand the detriment of lacking representation, both in your community and the media you consume. Reading banned books and helping others do so made sense to me.

Regardless, there’s a point to be made for our Constitution’s say in the matter, and that point is one Krug herself enforced from the beginning of her career:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Since book bans are state-enforced, we Californians don’t have much to worry about if we want to read The Hate U Give. Thankfully, it remains easy for us to gain access to titles on gender, sexuality, and race. However, as this year’s Banned Books Week came to a close, I found myself considering a title that often goes unmentioned in conversations about Banned Books, especially in our small blue bubble of California.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been one of the most heavily debated texts in the history of required readings. While some texts have been banned in efforts to protect conservative values, many liberal school districts have abandoned Huck Finn in an effort to prevent offensive language from entering the classroom. The reality is, book banning is a bipartisan issue.

“This Amazing, Troubling Book” by Toni Morrison is the essay that inspired this piece, and I recommend you read it when you get a chance. In it, Morrison — a heavily banned author herself — shares a wide range of ideas reflecting on Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. A critical focus of her essay is the criticality of the novel, as she details (much more eloquently than I am about to) why Huck Finn is a necessary text for classroom conversation.

Morrison’s primary concern with the discussion around Huck Finn is the oversimplification the novel receives when met with the blanket classification of ‘hate speech.’ When this happens, she argues, it threatens to oversimplify all of literature. And, despite its reprehensible language, Morrison argues Huck Finn is literature, and referring to it otherwise threatens the entirety of the literary and academic world. Sanitizing the story is to demolish its integrity. The derogatory language in the text is crucial to the plot and Jim’s character arc. And, as the title of her essay supposes, amazing and troubling do not cancel out each other. Much literature is horrifying and disturbing, and still beautiful. This does not exclude it from being literature.

Jim is the antithesis of the stereotype many white Americans thrust upon Black men. He is gentle, loving, and kind. Huck’s (white) father is abusive and absent, the way those same white Americans expected Black men to be. That is just one aspect of the plot line you lose when you abridge the novel or remove the offensive language and stereotypes. You will lose how terribly Jim is treated, and you will lose why it matters.

If we lose that aspect of the book, not only do we run the risk of erasing history, we erase the conversations that are necessary to have. Without classroom discussion on history and literature in its entirety, we don’t advance as a society. Moreover, we don’t expunge the racist ideology we need to in the classroom if we are still conditioned to believe this whitewashed version of history.

Wiping evidence of racism, sexism, bigotry, and the other issues that plague our nation’s past simply primes us for repeating history. It’s a dangerous game, and one that is not remotely constitutional to play.

Finally, critical engagement with challenging topics is essential in our education system. Especially as our world becomes more cruel, vile, polarized, political, rageful, and seething — we need to educate students about these topics. Students must learn how to navigate discomfort, anger, and disgust.

By shielding children from harsh conversations, we set them up to become prejudiced and closed-minded; not only ensuring them academic failure, but failure to succeed in life. We enable a society segregated by judgements. By removing debate topics, we remove debate. By removing debate, we remove thought. The way forward is not through ignorance, it’s through education and history, understanding and conversation, engagement and learning.

However, I say all of this not with the intent to throw caution to the wind. I agree with the notion that, without clarity and instruction, teaching Huck Finn holds a powerful opportunity to become a harmful experience, particularly for students of color. I believe that white educators should never read the n-word out loud and that the bigotry, racism, and language in the book must be part of the conversation in classrooms.

The reality of the matter is that this book is uncomfortable. It WILL create a tense classroom environment. It WILL spark fury and shock and disgust. But ultimately, sanitizing Huck Finn will sterilize the future of academia. As Morrison concludes in her essay,

“For a hundred years, the argument that this novel is has been identified, reidentified, examined, waged and advanced. What it cannot be is dismissed. It is classic literature, which is to say it heaves, manifests and lasts” (Morrison).