Poetry is an important form of human and literary expression. Though not applicable to all areas of the topic, poetry is often an art of limitations. Haiku forces writers to become creative with syllables, sonnets make poets dance to their meter, limericks through their rhyming structure and line limit, and so many other examples.

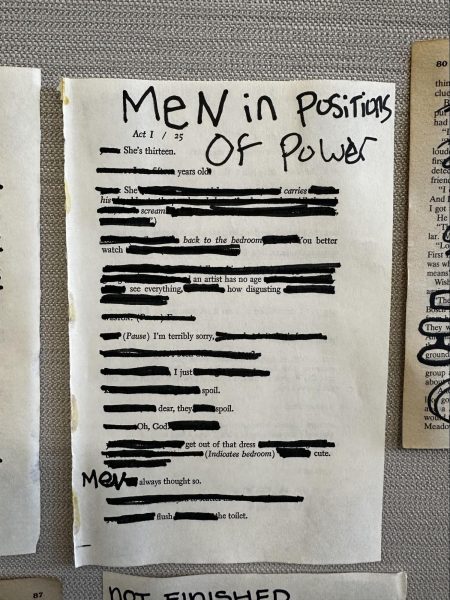

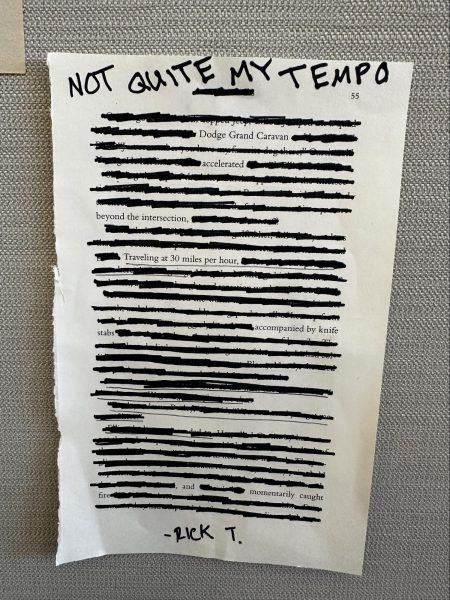

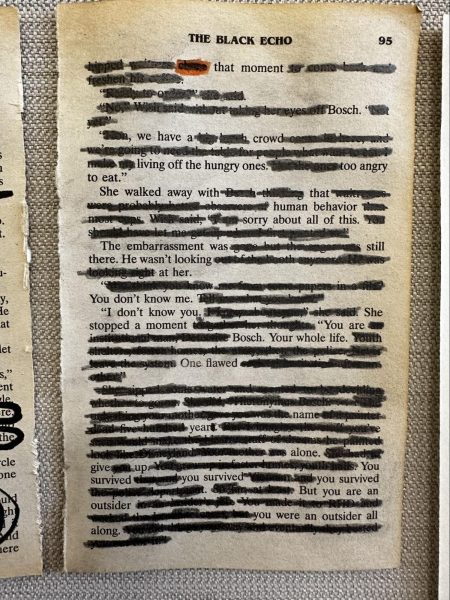

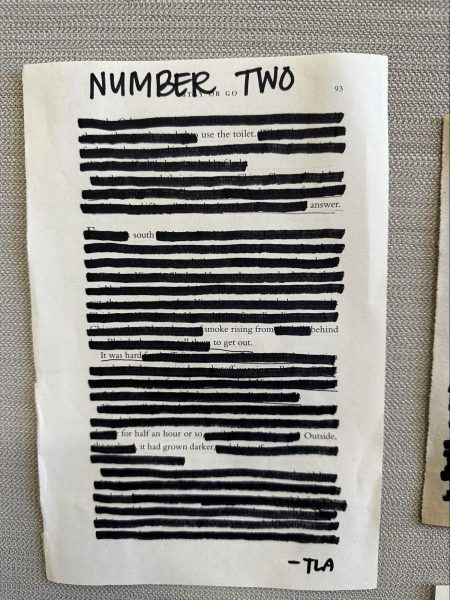

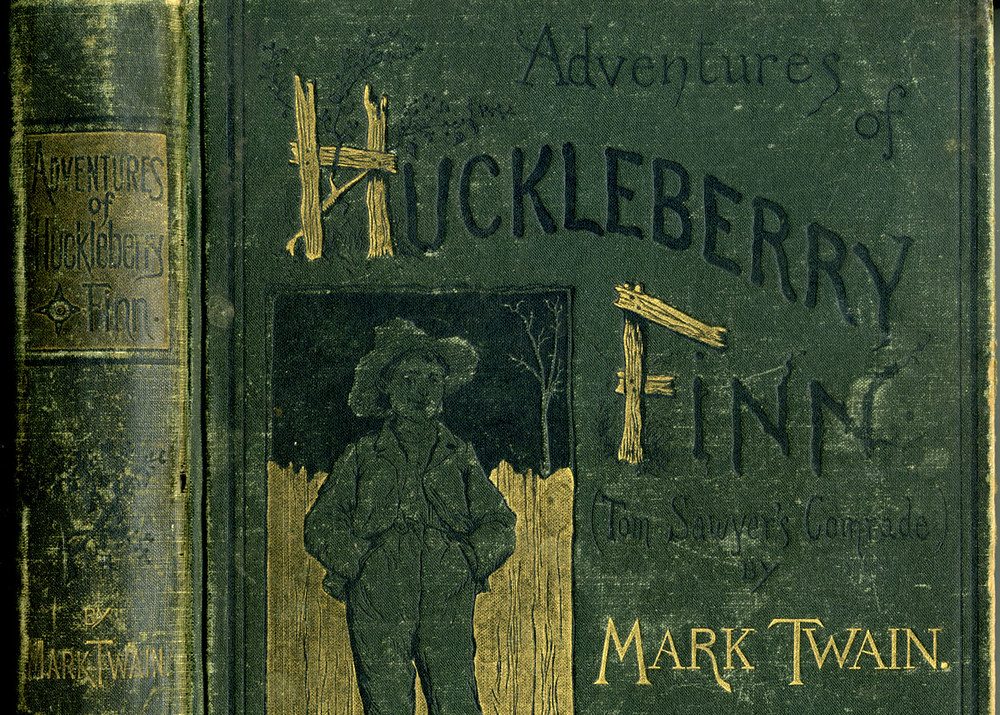

Blackout is a unique subsection of poetry that does not require the poet to actually write any words themselves. Instead, they take an already existing piece of text, and the blackout poet will then pick and choose which aspects to “blackout” and which to keep visible. This piece of text could quite literally be anything, so long as it is written. Newspapers, novel pages, a manuscript, a script, or even a magazine. As said before, poetry is often an art of limitations, and blackout poetry limits the artist through its reliance on subtraction. Typically, no new content is added to the piece of text you choose, and you must make do with what words, phrases, and punctuation are already present.

As an example, you might turn the sentence “The mischievous cat stealthily tiptoed across the sun-drenched patio, chasing shadows in its playful pursuit of adventure!” into “The sun chasing shadows in pursuit!” You could also change it into “cat-drenched, its adventure!”

This type of artistic expression encourages participants to unleash their creativity, exploring the interaction between words and visuals in a limiting and at the same time captivating way. Blackout poetry can not only be fun but could even be cathartic for some. It can be a form of transformation and reclamation, and not just a different take on something.

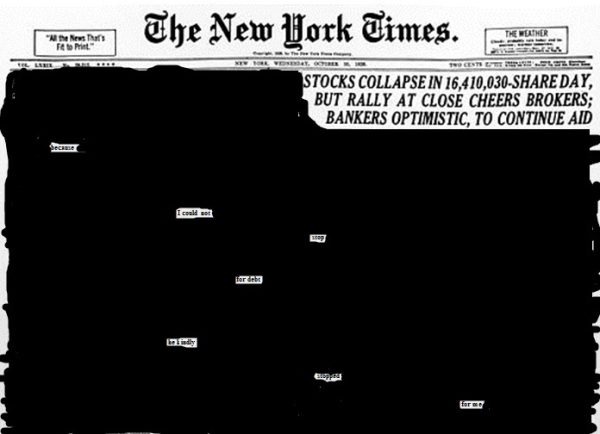

One famous example of this is a blackout poem done on a ‘The New York Times’ newspaper. This issue announced the coming of the 1929 stock market crash, kickstarting the Great Depression, with the headline “Stocks collapse in 16,410,030-Shareday, but rally at close cheers brokers; bankers optimistic, to continue aid” being left bare by the author. The bulk of the body text is blacked out, and only the phrase “Because I could not stop for debt, he kindly stopped for me.” remained, in reference to the famous Emily Dickinson poem “Because I could not stop for death.” The author transformed this media that reported something out of their control, and yet would affect their lives greatly, into something that could resonate with a great deal of people. Writers.com describes this piece beautifully, saying that “the poem can be interpreted as a critique of both speculative investing and the role journalism played in amplifying the crash.”

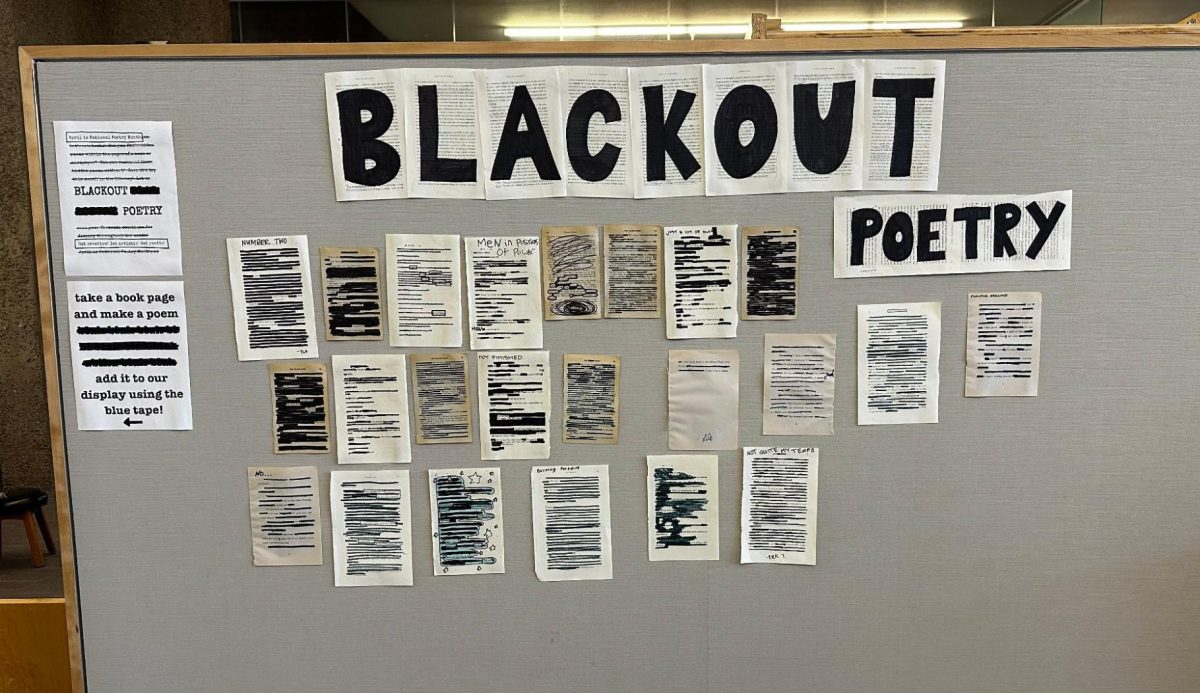

The staff at the library have graciously allowed students to express themselves on one of the short walls in the main hallway of the building, and there are currently an abundant amount of novel pages ready for your transformations! Over 20 people have currently participated, and our very own Editor in Chief, Nick Fletcher, was one of them! Go to the library and see if you can guess which one is his. Fair warning: it may give you a bit of whiplash once you figure it out!