Joker could inspire violence, but so could any other film

December 3, 2019

I don’t watch superhero movies.

I’m turned off by the interminable action sequences, the mindless explosions, the buildings that crumble so frequently they might as well be sandcastles. Twenty minutes into Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, I felt like I was watching a dramatized mash-up of tutorials for about 10 different forms of martial arts.

I’m not interested in the ultra-male Bildungsroman, the glamour of anonymous bodysuit-heroism, the cliche of the sidelined girlfriend forever perplexed by her playboy-by-day, vigilante-by-night. Which is why everyone told me I shouldn’t see Todd Phillips’ Joker. I was told I wouldn’t be able to appreciate it, not just because I don’t like violent movies, but because Joker is part of a mammoth comic-book universe that I have never been a part of.

In her review of the film in the Washington Post, Ann Hornaday wrote that Joker will ‘please the specific subculture of fans it aims to service, while those who have survived this long without caring about comic-book movies can go on not caring.’ I couldn’t disagree more.

I arrived at the theater braced for a bloodbath, and what I got was a sensitive, nuanced character drama that left me wishing I hadn’t written off superhero movies so often in the past.

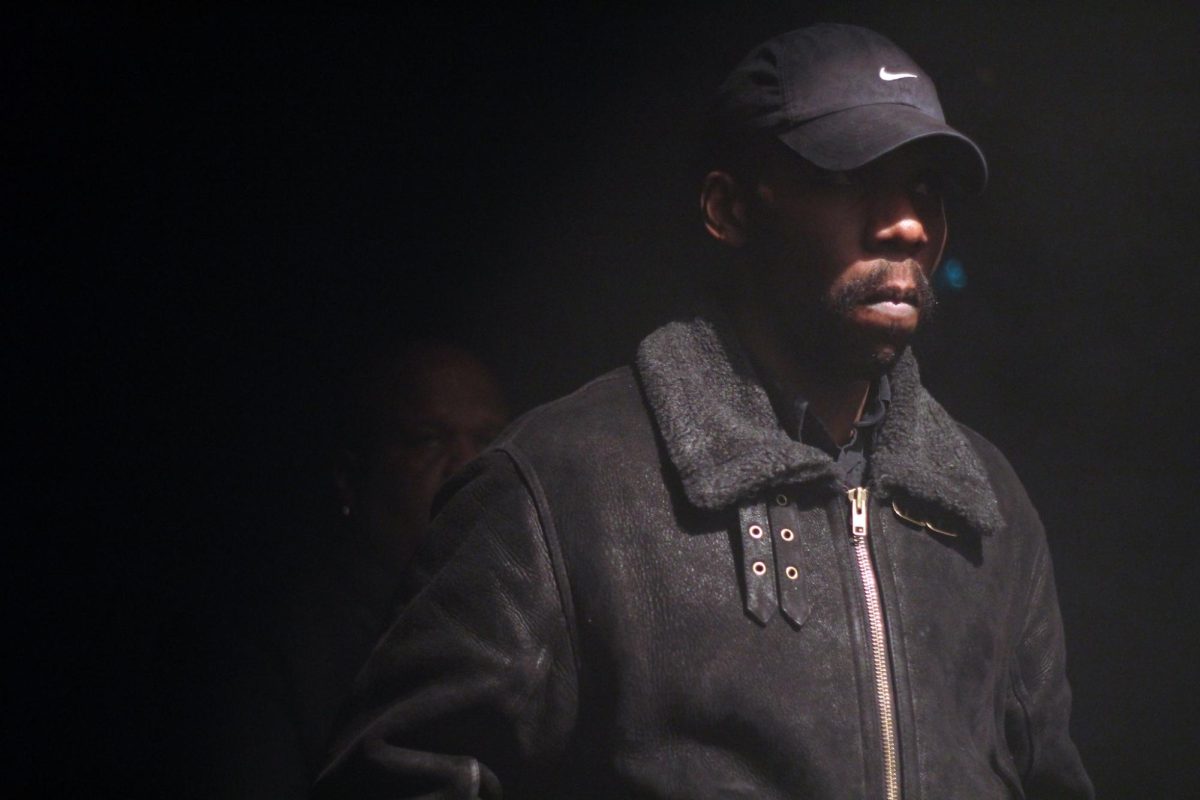

Joker is a gritty film, set in the anarchic city of Gotham. Arthur Fleck, an abused and lonely performer who dresses up in clown costumes and performs on the street, is at the bottom of the heap.

He is severely battered as a child and develops an involuntary, strangled laugh that bursts out of him whenever he is stressed or emotional. His illness is brutal to watch: it has the dual function of making him a victim and pariah in the story while also evoking sympathy in viewers. Joaquin Phoenix’s acting is not subtle and yet somehow intensely human – he inflects his maniacal laughter with a kind of laryngitic despair that bares his brokenness for all to see and hear.

He defies all categorization: he is neither a pity case nor a triumphant anti-hero; he is tortured but not predisposed to torture others – at least not at first.

The movie is well-paced, not rushing Arthur’s descent into insanity, taking care to knock down each domino one by one until the chain is irreversible: the verbal abuse, the street chases, the beatings, the mockery, the cutting of government funds that supply Arthur his meds and therapy, and perhaps most chilling in its relevance – his effortless acquisition of a gun.

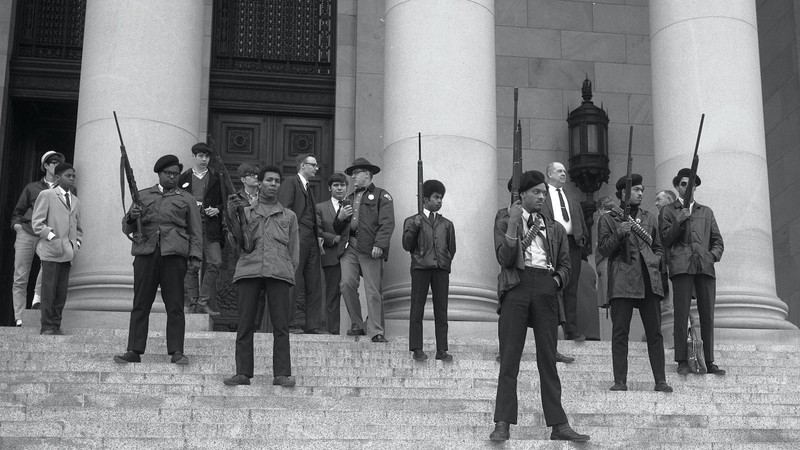

This sense of inevitability that pervades the film has garnered heavy criticism; the Economist’s review describes the movie as ‘a two-hour wait for (Arthur) to put on his colorful suit, smear on his white make-up and start shooting people.’ Which brings us to the loudest and perhaps most urgent controversy surrounding this film: does it encourage mass violence?

Before watching Joker, my answer was a wholehearted “yes.” I didn’t understand why we, a country perpetually in mourning for mass-shooting victims and still freshly grieving the deaths in Dayton, El Paso and Santa Clarita, needed another movie about why we should feel sorry for psychopathic murderers.

In general, I don’t believe artists should be held responsible for viewers’ reactions to their art, but my central question surrounding Joker was why? Why spend more time pondering the psychology of mass-killers? Why give these kind of sadists a platform, a space to shine?

Don’t these kind of ‘society-broke-him’ narratives bear a disturbing resemblance to the excuses we hear on behalf of men like Brock Turner and Daniel Pantaleo? Whether the crime is sexual assault on a college campus or killing a man with an illegal chokehold, statements like ‘but he was a hard worker’ or ‘he was talented’ or ‘he was threatened,’ do nothing but insult victims and minimize the damage done to them.

These were the thoughts running through my head when I sat down to watch Joker. But as the film progressed, my feelings changed. Phillip’s meticulous, character-driven storytelling, combined with Phoenix’s phenomenal acting, led me to see Arthur Fleck not as some political symbol or stand-in for a real-life villain, but as simply a character in a story.

We all know the Joker as the blood-crazed lunatic from the Batman saga, a miscreant who derives his own twisted comedy from other people’s tragedy. Joker, like all origin stories, is a creative exploration of a character who would otherwise be fairly one-dimensional and easy to pathologize.

If I lived in a social vacuum, and all I had to worry about while watching this film was whether or not it made me feel something, then Joker was an overwhelming success. I left the theater shivering, not just because I was spooked, but because Phoenix’s portrayal of mental illness struck a chord, and struck it hard.

At times, I agreed with the Economist in that Arthur’s cyclical, preventable suffering felt a little bit like rubbing salt in a wound we already know is never going to heal. But regardless of whether or not the violence was excessive – there were moments I think could have been cut back – Philips and Phoenix led me to feel for Arthur Fleck without romanticizing his rampages. If anything, they did the opposite: Phoenix’s unflinching embodiment of isolation and illness, coupled with Phillip’s prioritizing of character and story over grisly action sequences, made Arthur’s descent into violence all the more harrowing.

When I was little, I loved writing stories about the villains in fairy tales. There were already so many versions of how Cinderella got to the ball, how Sleeping Beauty pricked her finger, how Rapunzel escaped her tower. I was more interested in why Maleficent was so lonely, why Mother Gotham was so desperate to have a daughter and never let her out of her sight.

This is what writers do: find interesting characters and live inside their heads for awhile. This is what Phoenix did with Arthur Fleck, and he did it masterfully.

Of course, readers and viewers can always respond by pointing out that we don’t live in a social vacuum. What artists make does influence the way people think, feel and behave. So if the question is, “Does Joker have the potential to inspire violence?” my answer is still yes.

Any film has the potential to inspire any kind of reaction, but artists can’t thrive under the pressure of that knowledge. An artist’s job is to create, and however people choose to interpret or act in response to a piece of art is their own responsibility.

Should directors consider the impact of the messages they communicate through their films? Yes. Should writers be mindful of the power they wield with their words? Of course. But often, painful truths that films and stories unearth are powerful, precisely because we don’t live in a vacuum.

Arthur’s killing sprees are particularly disturbing because they were in part, provoked by things people of all ages, personalities and backgrounds face in the U.S. everyday: lack of access to health care and easy access to guns. The film is not subtle about the havoc these factors can wreak.

So, I don’t watch superhero movies.

Whenever I watch a movie containing graphic violence, my question will always be “why?” and it is the job of the director and actors to convince me that it is not gratuitous – that it is indeed serving the story.

But I watched Joker, and as a first-time traveler into the comic-book universe, I was enthralled. I got to explore the psychology of a fascinating character living in a world whose brokenness mirrors our own in so many ways. So my new question is: why not?