Petroleum & Permafrost: Impacts of The Senate Tax Plan

Early on the morning of Saturday, December 2nd, Senate Republicans successfully passed their version of a sweeping tax overhaul bill. The bill passed largely along party lines, receiving a 51-49 vote, with only a single dissenting Republican. While it has endured many amendments, one particular portion proposed is a source of great alarm for many environmentalists: the bill seeks to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, located in Northern Alaska, to oil drilling.

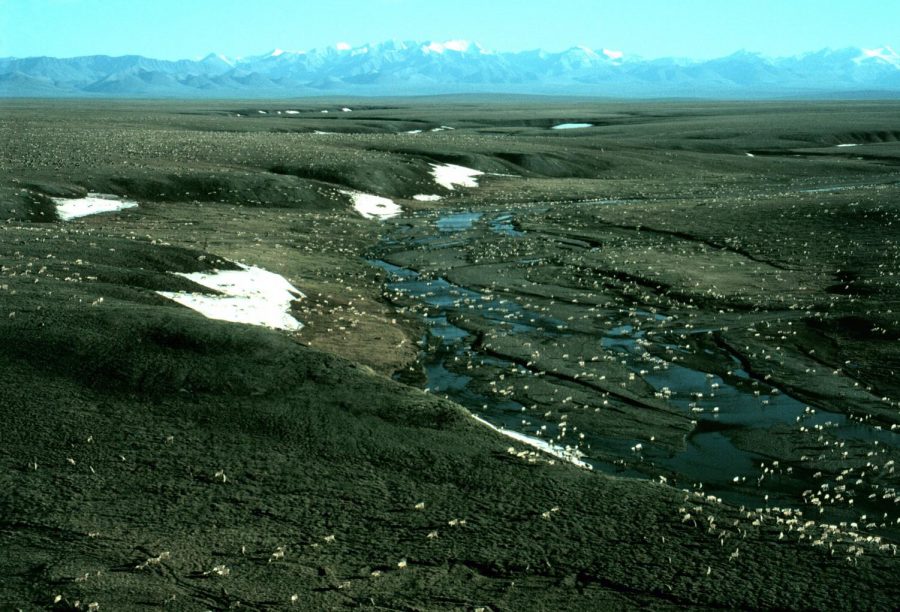

The refuge, which spans nineteen million acres, and is the largest wildlife refuge in the United States, was first established as the Arctic National Wildlife Range in 1960 “to preserve unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values.” In 1980, it was re-designated as a refuge with designs to preserve ecological diversity and water quality and quantity.

With this change, however, came the additional designation of “1002 Area,” which encompasses 1.5 million acres of the Arctic’s coastal plains. This legislature allowed for the cataloguing of fish and wildlife resources, in addition to research studies relative to petroleum. It also prohibited the development of the land for purposes of natural gas production — and since 1980, the region has gone untouched. There are no roads in the refuge, and fewer than five hundred people living in its close vicinity.

Senator Lisa Murkowski’s amendment to the Senate’s tax bill has the potential to change all of this, though. Both Alaska’s state and the Federal government seek to reap benefits from increased oil flow into the United States by way of drilling in “1002 Area.” The revision would generate five billion dollars over the next decade in revenue for the Federal government, according to the Congressional Budget Office — which more than fulfills the Senate Budget Committee’s request for one billion dollars in revenue to help close the budget deficit. However, the merit of this revenue influx is being challenged by many democrats and fiscal conservatives — as the tax plan overall would add another $1.5 trillion to the deficit in the same period, drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge would hardly make a dent.

For the state of Alaska, however, drilling in the region has far more significant implications. As Alaska maintains no state income or sales tax, the state is highly dependent on petroleum as a source of revenue; the commodity has averaged more than eighty-five percent of the state’s budget since 1977. According the the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, petroleum also supports a third of all jobs in the state.

And while Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK,) chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, acknowledges the gravity of climate change — and earlier this year discouraged President Trump from withdrawing from the Paris agreement — she also believes that drilling in the region is necessary to the state’s economy, and that the answer that bridges the gap between environmentalism and pragmatism is using revenues from oil to help create alternative energy resources.

Kara Moriarty, President and CEO of the Alaska Oil and Gas Association, is supportive of the amendment to the tax bill, and reassures that “the oil industry…[will be]…keeping most of its activities in a stark, treeless 2,000-acre region on the coastal plain that is far away from the majestic vistas that often illustrate ANWR discussions.”

However, just because a region is “stark,” “treeless,” and not deemed a majestic vista, doesn’t mean that drilling won’t have a significant environmental impact. The Arctic Coastal Plain regions of the refuge have a “greater degree of ecological diversity than any other similar sized area of Alaska’s north slope,” and “roads, pipelines, gravel mines, and well pads” erected by mining companies would impact caribou mothers and polar bear dens.

Aside from altering complex ecosystems and endangering particular species, drilling for oil in the region also contributes to climate change. It’s commonly accepted that burning fossil fuels creates greenhouse gas emissions — since the beginning of the industrial revolution, these forces have warmed the earth by more than one degree Celsius. According to 2012 studies, eighty percent of fossil fuels we can already access must remain untouched to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius.

In Alaska, a state that is warming twice as fast as the rest of the country, drilling for oil could also do significant damage to the layer of permafrost that lies underneath eighty-five percent of the state’s land. Permafrost is a layer of frozen ground that begins just a few feet below ground level and can extend downward hundreds of feet. Oil and gas exploration can have potentially disastrous effects on this layer by way of construction and its resulting dust deposition, which reduces the reflectivity of the snowy surfaces and increases absorption of solar radiation, thereby furthering melting.

Despite being “stark” and “treeless” according to Moriarty, the region slated for oil exploration is also one where permafrost is preserved by the lack of human activity in the region. Although permafrost is most vulnerable 350 miles south of the Arctic Circle, in a similarly treeless landscape formed by sediment, that isn’t to say that permafrost further north isn’t at risk.

And when this layer of ground does melt, it will have disastrous results on many fronts. On the simplest level, the thawing can cause significant infrastructure damage by way of erosion when ice turns liquid, leading to sunken buildings — according to one study, the damage may total $5.5 billion by the end of the century.

Most significantly to climate change, permafrost is also a haven for carbon and methane: the layer currently traps 1,400 billion tons of carbon, which is double the amount that is currently in our atmosphere. When permafrost melts, carbon is released, further raising temperatures and resulting in further warming.

And as permafrost has been frozen for hundreds of thousands of years, the layer of ground contains ancient organic matter, including bacteria and viruses that modern humans haven’t encountered yet. This creates a dangerous environment for workers involved in mining projects that disrupt the layer, in addition to native plants and animals.

According to a congressional audit, global warming has already cost the country billions of dollars; if warming continues, governments near the coast will need to protect against floods and storm surges, which will increase these expenses. This is especially pressing considering an Arctic Council report which says that by 2040, twenty percent of permafrost near the surface may melt. And while declining revenue almost lead to a state government shutdown in Alaska this summer, incentivising increased petroleum production, Alaska’s tourism economy generates more jobs than oil, framing an alternative for state revenue that prioritizes climate conservation.

By limiting federal land leasing for fossil fuel production, greenhouse gas emissions could be significantly stunted. Whether Alaska’s state government considers this benefit to take priority over the status quo of the state’s dependence on fossil fuels or not could be the deciding factor of both the state’s geographic composition and the fate of the tax bill which incentivizes state support via increased access to petroleum-rich regions.

Kathy

Dec 7, 2017 at 7:56 pm

Curious about how drilling vs not-drilling impacts the people of Alaska.