International Education Week: From Foster Youth to Fostering Connections

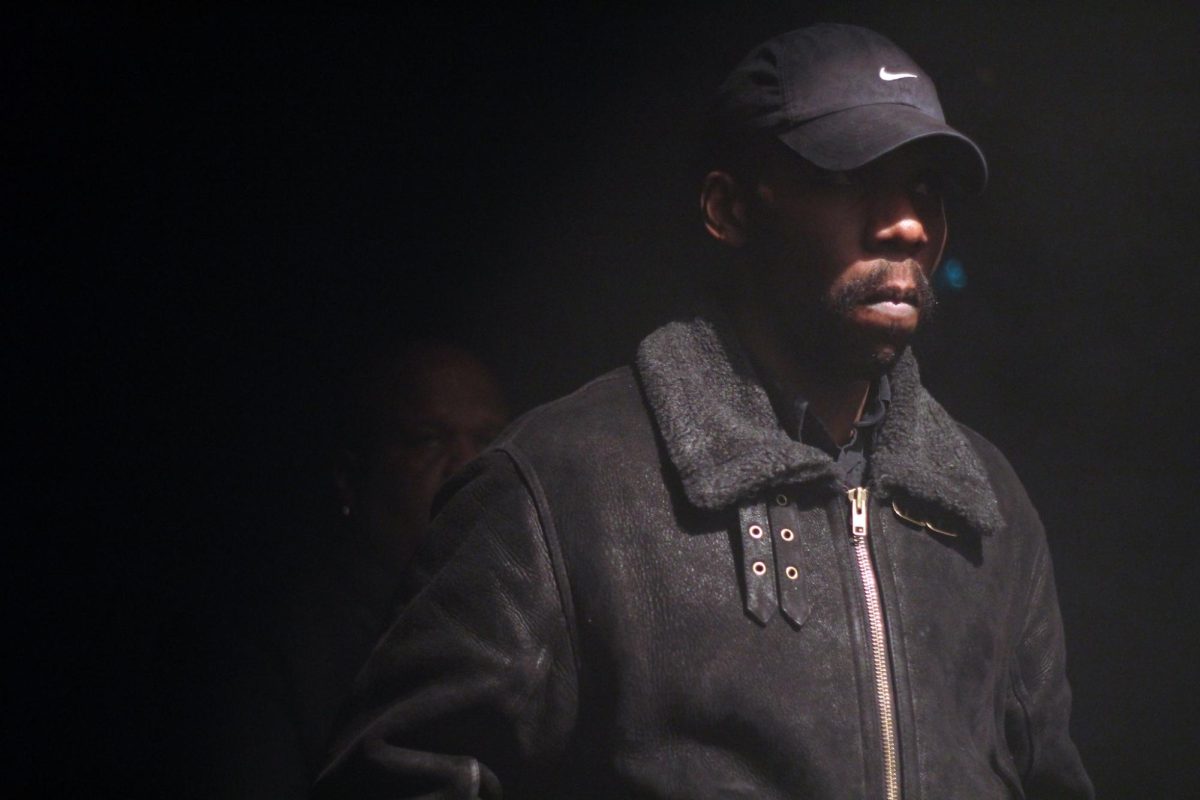

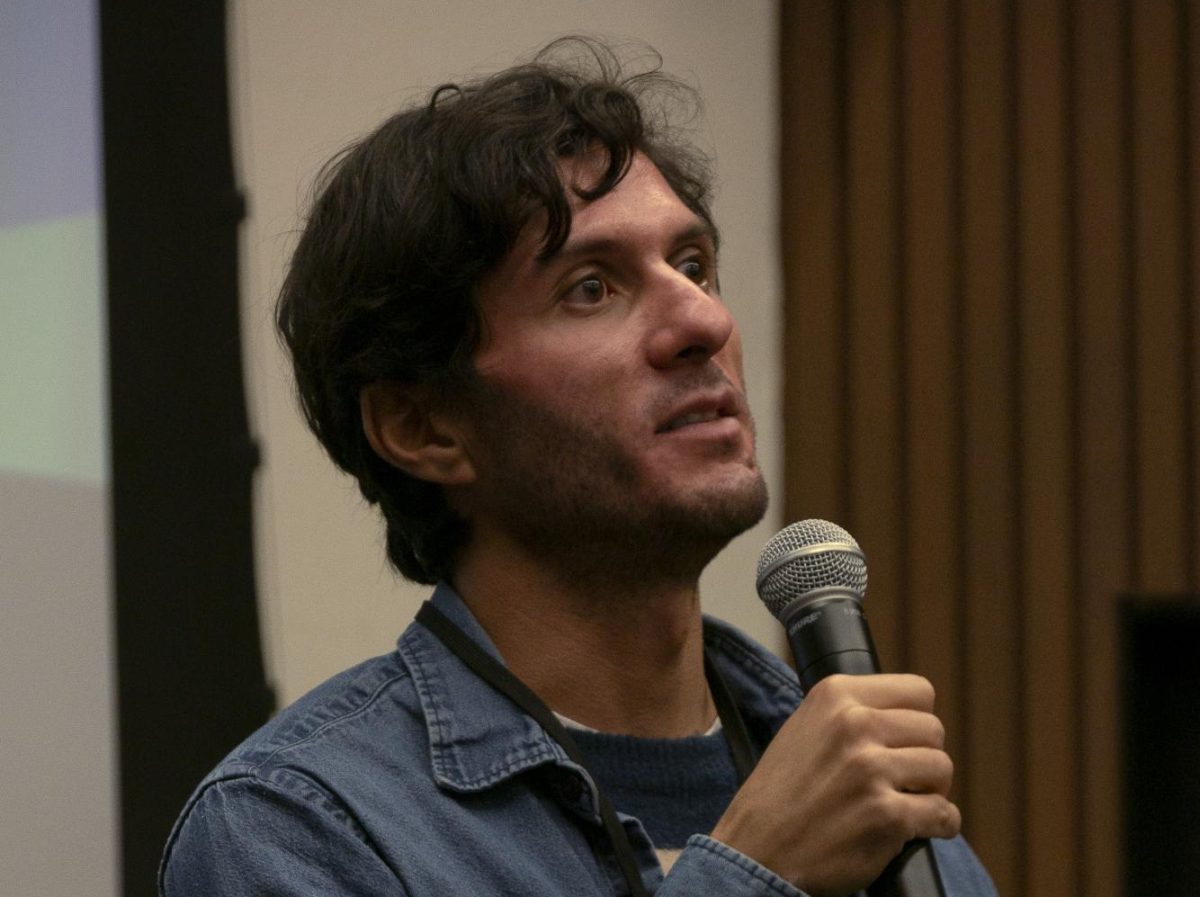

Have you ever thought that a simple conversation could lead to your meal being paid for? Or how complimenting someone on his/her shoes could actually get you the shoes? I never really thought about it either — maybe because it sounds like it only happens in movies — until I met one of Foothill’s International Education Week speakers, Carlos Collard.

I first met Carlos Collard inside the Hearthside Lounge just before the talk started; he confidently greeted me with “Apa kabar?”, which means “How are you?” in Bahasa Indonesian, just after I told him where I came from. I was quite impressed — I have been to other countries and different parts of the U.S. but no one has ever greeted me in my mother tongue.

For International Education week, Collard shared his experience and life lessons growing up as a first generation college graduate and former Los Angeles foster youth. He was only two years old when his biological mother kidnapped him from The Collards, his warm foster family that had taken care of foster children for years. The Collards began searching for him until they found him and gained full custody of him.

Collard attributed his life to those who showed compassion toward him growing up, “That’s why I’m here. Because people cared about me.”

The Collards then moved to what was called “The Land of Promise”, also known as California. Soon, approximately 200 foster kids circulated in and out of the house. Out of the 200, six children were adopted, including Collard.

“A stable home and people who care about me,” Collard said. “That’s all I need to begin with.”

When Collard was in tenth grade, he told his high school counselor that he wanted to go to one of the most competitive schools in the country, the University of California, Los Angeles. Devastatingly, the counselor replied, “No you can’t, your family doesn’t have the money to pay for college. You should go into the military.”

That didn’t stop Collard from following his ambitions. Despite the fact that no one in his family had attended college, they provided an environment conducive to achieving his dream. Proving his counselor wrong, Collard’s hard work and immense support from his family earned him a spot at UCLA.

The first year wasn’t as smooth as he wished it would be: he felt out of place, but this pushed him to search for resources to help him succeed, like those available for first generation, low income students. During his senior year at UCLA, Collard’s father passed away and he delayed his graduation. The death of his father reminded him about what his parents had gone through just so he could live.

“If I share my story, I can have a larger impact,” Collard said. “Like what happened to me.”

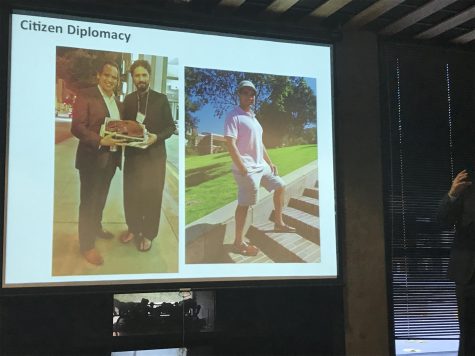

Collard started to realize these things and he changed his perspective when it comes to making connections. At the end of college, he began attending cultural performances and exhibitions and decided to get involved. From then, he started seeing “the world.” Collard, who is also a citizen diplomat, now takes part in hosting leaders from all over the world nominated by the U.S. Embassy. During the talk, he shared a memorable story from his experience as a citizen diplomat: a Pakistani man was wearing sandals from his country that looked unique to him.

Collard simply said, “Hey, those are cool sandals.”

“Oh, do you want them?” the man replied.

“No, I’m just gonna take a picture of them,” Collard said.

Not long after that, the Pakistani man returned with the sandals in a box.

“I have something for you. It’s my sandals. I want you to have them.”

This experience has taught Collard that, this is the kind of things that happened when you show interest and genuine curiosity. Collard mentions that having conversations, especially with people whose countries have “bad reputations”, could surprise both parties.

“When Americans treat them with respect, it might be a bit [of a] shock for them,” Collard said.

Another interesting story Collard shared was a time he visited his doctor’s office. He saw a nurse wearing a necklace that to him seemed really

unique. Without hesitation, he asked her it was from.

“Oh, it’s from Ethiopia,” the nurse said.

A conversation ensued, and Collard was invited to an Ethiopian festival in Los Angeles. Collard admitted that he might not be fluent, but knows how to say hello, thank you and how are you in more than one hundred languages.

“If you could just say hello or thank you, that goes such a long way,” Collard said.

Growing up in a multicultural family with few possessions has taught him how to foster these kinds of connections with people. The Collards treated all the children in the house equally, no matter where they came from.

“My parents treated everyone like a person,” Collard said. “That helps me make connection because I … don’t define by their status or wealth. I see that everybody has lived life and has something you can learn from. If you go [into] meeting new people with that mindset, it helps you make connections.”

To all Foothill students, Carlos Collard has a special message:

“Every opportunity is one that you can make the most of. You can do great things anywhere. There are plenty of opportunities to be a leader here and volunteer, [and] you have resources here [at] Foothill that [some] … community colleges don’t have. But also … not a lot of school[s] have high international populations. Take advantage [of] learning about the people here. It opens up horizons, friendships and new connections from other countries.”

The power of reaching out to people goes a long way, and Foothill College is a great place to start.